Women who deliver preterm are at a higher risk of developing ischemic heart disease (IHD) independent of other risk factors like BMI or smoking, reports a new study.

‘Women with a history of preterm delivery may warrant early preventive actions to decrease other ischemic heart disease risk factors.

’

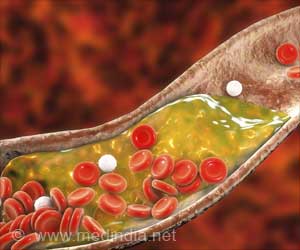

Preterm delivery occurs in about 9.6% of births in the U.S. annually and is defined as any birth that occurs at less than 37 weeks. Women who deliver preterm have been found to have increased future risks of hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, which are huge risk factors for IHD. While previous studies have shown associations between preterm delivery and future risks of IHD, the long-term risks of IHD for women across their life course, and how they vary by pregnancy duration has remained unclear. Furthermore, the relative contributions of shared familial (genetic and/or environmental) factors vs. direct effects of preterm delivery on the development of IHD have not been evaluated. This is the first study to assess the potential influence of unmeasured familial factors on associations between preterm delivery and future maternal risk of IHD. Researchers used the Swedish Medical Birth Registry, which contains nearly all prenatal and birth information for deliveries in Sweden, to examine long-term changes in IHD risks in women who gave birth, with up to 43 years of follow-up, between 1973-2015. The researchers identified and studied 2,189,190 women who had singleton deliveries during the assessment period. Co-sibling analyses were performed among all 1,188,730 women (54.3%) with at least one sister who had a singleton delivery. The pregnancy duration observed included six groups: extremely preterm (22-27 weeks), very preterm (28-33 weeks), late preterm (34-36 weeks), the early term (37-38 weeks), full-term (39-41 weeks, study's reference group) and post-term (42 weeks or more). Additionally, the first three groups were combined to provide summary risk estimates for preterm delivery.

In 47.5 million person-years of follow-up, 49,955 (2.3%) women were diagnosed with IHD. In the ten years following delivery, women who delivered preterm or extremely preterm had ~2.5- and four-fold risks of IHD, compared with those who delivered full-term, after adjusting for other maternal factors including preeclampsia, diabetes, high BMI and smoking. Early-term delivery also was associated with an increased risk of IHD (~1.4-fold). These risks subsequently declined but remained significantly elevated even 30-43 years after delivery. Results from the co-sibling analyses suggested that these findings were not attributable to shared genetic or environmental factors in families.

"Preterm delivery should now be recognized as an independent risk factor for IHD across the life course," said Casey Crump, MD, Ph.D., a lead researcher of the study and professor of family medicine and community health at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. "Cardiovascular risk assessment in women should routinely include reproductive history that covers preterm delivery and other pregnancy complications. Women with a history of preterm delivery may warrant early preventive actions to reduce other IHD risk factors, including obesity, physical inactivity, and smoking, and long-term monitoring for timely detection and treatment of IHD."

This study has several limitations, including the unavailability of detailed clinical data to verify IHD diagnoses; information on outpatient diagnoses wasn't available until 2001, resulting in underreporting of IHD; and the possibility of incompletely controlled confounders such as maternal smoking, BMI or other IHD risk factors during pregnancy, which may have influenced results. Since this study was limited to Sweden, it will need replication in other countries, including racially diverse populations to explore for potential heterogeneity of findings.

Advertisement

"The higher IHD risk in women who had preterm birth persisted in co-sibling analysis, suggesting that shared genetic or environmental factors did not underlie the association with IHD. The novel results are a call to action for further development of the field of cardio-obstetrics."

Advertisement