The chief ingredient of blood clots is a remarkably versatile polymer called fibrin.

The chief ingredient of blood clots is a remarkably versatile polymer called fibrin. This polymer forms a network of fibers or a blood clot that stems the loss of blood at an injury site while remaining pliable and flexible.

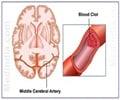

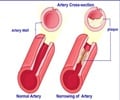

On the other hand, fibrin provides a scaffold for thrombi, clots that block blood vessels and cause tissue damage, leading to myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and other cardiovascular diseases. How does fibrin manage to be so strong and yet so extensible under the stresses of healing and blood flow?The answer is a process known as protein unfolding, report Penn researchers in Science this week. An interdisciplinary team, composed of investigators from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, the School of Arts and Sciences, and the School of Engineering and Applied Science, has revealed how protein unfolding allows fibrin to maintain its remarkable and contradictory characteristics. Understanding blood clot mechanics could help in the design of new treatments not only to prevent or remove clots that cause heart attacks and strokes but also to enhance blood clotting in people with bleeding disorders. Fibrin's unusual characteristics may also lead to applications in designing new synthetic materials based on its biology.

Building on previous work examining the properties of fibrin, senior author John Weisel, PhD, Professor of Cell and Developmental Biology, and his collaborators studied the mechanics of fibrin clots under stress from the macroscopic scale down to the molecular level. The results were achieved by joint efforts of scientists with different skills, knowledge, and backgrounds: A graduate student Andre E. X. Brown and his adviser Professor Dennis E. Discher brought physics and biomedical engineering; Senior Investigator Rustem I. Litvinov provided his expertise in protein chemistry and medicine; and Prashant K. Purohit, an Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering, joined the team to perform theoretical analyses of the experimental data and construct mathematical models of what was happening.

The researchers found that individual fibers in a fibrin blood clot are normally randomly oriented in an intricate meshwork pattern. But when the clot is stretched, the fibers begin to align with each other in the direction of the stress. As the strain continues, the clot stretches and gets longer -- but its volume actually decreases, which surprised the scientists. "That's very unusual," notes Weisel. "It's a property that's been found in a few other materials but it's very rare."

This was a sure sign that something unexpected was going on. "Slipping past each other between or within fibers was not a possibility that could give rise to such high unusual extensions because these fibers were cross-linked. This research provides evidence, both in terms of the mathematical model and with x-ray scattering data, that there is indeed unfolding going on," Purohit says."

The team used a variety of techniques from simple controlled stretching to electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction, atomic force microscopy, and mathematical modeling, to provide a coherent picture of how fibrin clots behave from the centimeter to the nanometer scale. This multi-scale strategy was vital: "You have to examine events at different spatial scales with various methodologies to understand how fibrin behaves," explains Weisel.

Advertisement

That expulsion of water was a surprise, Weisel says. "The volume change, the fact that it's so extensible, that wasn't known previously. At the molecular level this unfolding is necessary for the mechanical properties."

Advertisement

Beyond the obvious medical benefits, the team's interdisciplinary approach highlights the relevance of the research to other fields, such as biomedical engineering and materials science.

Source-Eurekalert

RAS