Scientists have discovered a 50 percent increase in total mortality and three-fold increase in heart disease deaths in persons with high urinary levels of 3-PBA, a metabolic product of pyrethroids indicative of human exposure.

‘Pyrethroid pesticides are ubiquitous, and exposure is unavoidable; in New York City and elsewhere, aerial spraying for mosquito control to prevent West Nile virus and other vector-borne illnesses is largely based on pyrethroids.’

Pyrethroid pesticides are a large family of synthetic analogues of naturally occurring pyrethrins that are also widely used in numerous consumer products. Collectively, they are the second most-used insecticides in the world, totaling thousands of kilograms and billions of dollars in U.S. sales. According to Steven Stellman, PhD, Columbia professor pf Epidemiology, and Jeanne Stellman, PhD, professor of Health Policy and Management, this unexpected finding of increased risk of death from exposure to such a commonly used agent merits urgent follow-up.

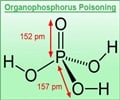

Unlike pesticides, such as DDT and dieldrin, which can persist in adipose tissue for decades, the biomarker 3-PBA has a very short half-life, as low as 5.7 hours. The prevalence of detectable levels of a rapidly eliminated pyrethroid metabolite in a large, geographically diverse population is suggestive of chronic exposure, which also makes it important to identify specific environmental sources, note the Stellmans.

However, caution is needed in interpreting the original study published by the University of Iowa School of Public Health. First, data were available only on adults aged 20-59 years at baseline, so that the average age at the end of follow-up was approximately 57 years, which is young for assessing cardiovascular mortality effects.

Other than cigarette smoking, few, if any, chemical exposures are known to trigger a 3-fold increase in the risk of death from heart disease, especially in persons younger than 60 years, suggesting that other, as yet unknown, factors may be associated with these increased risks. Further detailed studies based on validated exposure assessment methods, including both questionnaires and biomarkers, are needed to assess these toxicological parameters. This study challenges the assumption that such exposures are safe.

Advertisement