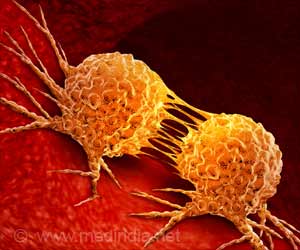

Researchers have discovered that radiation exposure can alter the environment surrounding the cells so that future cells are more likely to become cancerous.

"Our work shows that radiation can change the microenvironment of breast cells, and this in turn can allow the growth of abnormal cells with a long-lived phenotype that has a much greater potential to be cancerous," says Paul Yaswen, a cell biologist and breast cancer research specialist with Berkeley Lab's Life Sciences Division.

Studies have shown that if a cell develops a pre-cancerous phenotype, it can pass on these "epigenetic" changes to its daughters, just as it can pass on genetic mutations.

"Many in the cancer research community, especially radiobiologists, have been slow to acknowledge and incorporate in their work the idea that cells in human tissues are not independent entities, but are highly communicative with each other and with their microenvironment. We provide new evidence that potential cancer agents and their effects must be evaluated at a systems level," said Yaswen.

"The work we did was performed with non-lethal but fairly substantial doses of radiation, unlike what a woman would be exposed to during a routine mammogram. However, the levels of radiation involved in other procedures, such as CT scans or radiotherapy, do start to approach the levels used in our experiments and could represent sources of concern," said Yaswen.

For the study, researchers worked with human mammary epithelial cells (HMECs), the cells that line breast ducts, where most breast cancers begin.

Advertisement

However, also present are rare variant HMECs, which display a phenotype that allows them to continue dividing for many weeks in culture.

Advertisement

To test the effects of radiation on cellular environment and subsequent cell behavior, the research team grew sets of HMECs from normal breast tissue in culture dishes for about a week, then exposed each set to a single treatment of a low-to-moderate dose of radiation.

They then compared the irradiated sets to sets of breast cells that were not irradiated.

Four to six weeks after the radiation treatments, most of the cells in both the irradiated and unirradiated sets had permanently stopped dividing.

"However, the daughters of breast cells exposed to radiation formed larger, more numerous patches of cells with the vHMEC phenotype than did the daughters of the unirradiated cells. An agent-based model developed by Sylvain Costes and Mary Helen Barcellos-Hoff suggests that the radiation increased the rate at which short-lived cells became senescent," said Yaswen.

In a culture dish, breast cells will only divide and grow so long as there is room for daughter cells to spread out.

When the dish becomes full, the cells stop dividing. By promoting premature senescence in the normal HMEC, the radiation treatments accelerated the outgrowth of the vHMECs.

"Radiation exposure did not directly induce new vHMECs and the effect was not dose-dependent in the dose range we investigated. However, by getting normal cells to prematurely age and stop dividing, the radiation exposure created space for epigenetically altered cells that would otherwise have been filled by normal cells. In other words, the radiation promoted the growth of pre-cancerous cells by making the environment that surrounded the cells more hospitable to their continued growth," said Yaswen.

The study appears in the on-line journal Breast Cancer Research.

Source-ANI

THK