Genetic differences between two similar species of the pathogenic Cryptosporidium parasite have been discovered by researchers.

"Being able to discriminate quickly between the two species means it is easier to spot an outbreak as it develops, trace the original source, and take appropriate urgent action to prevent further spread," said lead author Dr Kevin Tyler of Norwich Medical School at UEA.

Cryptosporidium is a protozoan parasite that causes outbreaks of diarrhoea across the globe. In the UK, around two per cent of cases of diarrhoea are caused by the organism and many people will be infected at some time in their lives. Symptoms include watery diarrhoea, stomach pain, nausea and vomiting and can last for up to a month, but healthy people usually make a full recovery.

However, in the developing world infection can be serious in malnourished children and a significant cause of death in areas with high prevalence of untreated AIDS.

In the UK, outbreaks have been caused by faulty filtration systems in water supplies and transmission through swimming pools because the parasite is not killed by chlorine disinfection. Outbreaks also occur at open farms and in nurseries. People can also be infected by eating vegetables that have been washed in contaminated water. Hygiene is important in the prevention of spread of Cryptosporidium: people are advised to always wash their hands with warm running water and soap after touching animals, going to the toilet, changing nappies and before preparing, handling or eating food.

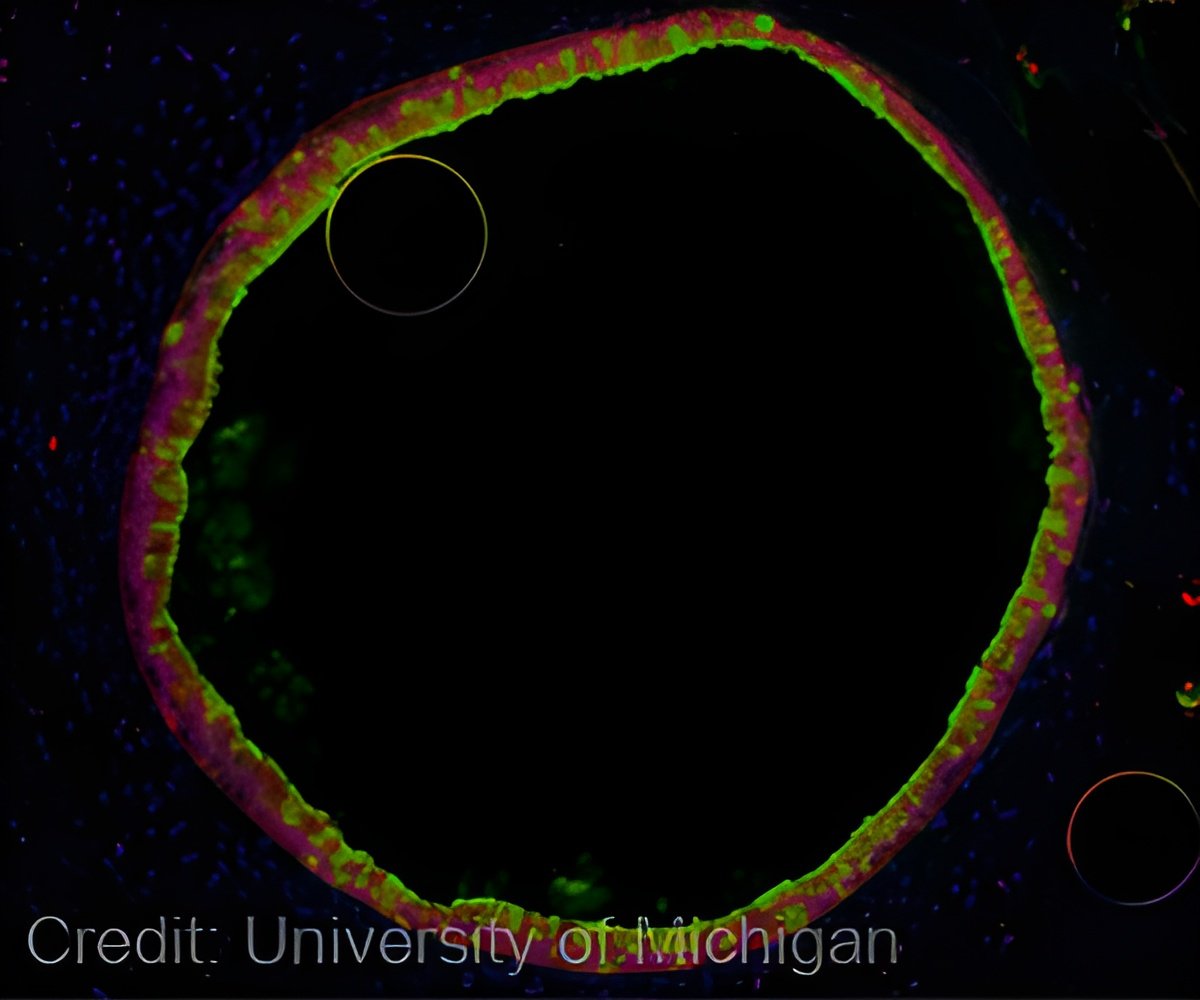

In this EU-funded study, the researchers identified the first parasite proteins that are specific to the different species. They found them at the ends of the chromosomes where they had been missed during previous parasite genetic studies.

Advertisement

The UEA team worked with colleagues at the UK Cryptosporidium Reference Unit in Swansea, and Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, part of Queen Mary, University of London. Recently obtained renewed funding from the EU will enable further development towards a diagnostic test for use in the water industry and public health.

Advertisement