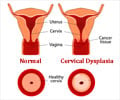

Cervical cancer prevention relies on two different age-specific technologies, and consumers should not be misled about the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines.

Cervical cancer prevention relies on two different age-specific technologies, and consumers should not be misled about the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines, according to an article in the latest edition of The Medical Journal of Australia.

Dr Gerard Wain, from the Department of Gynaecological Oncology at the Westmead Hospital in Sydney, said HPV vaccines are about preventing future infections while cervical cytology detects cytological abnormalities from previous infections.“It is important that the benefits of these two approaches to cervical cancer prevention are not confused, and that all women receive the best and most appropriate combination of the two effective technologies,” he said.

“The link between HPV infection and the consequent risk of developing cervical cancer is well documented. The promise of a cancer vaccine is alluring to women who perceive a risk of cervical cancer, but we have to make sure that the available vaccine does not promise to deliver beyond its capacity.”

Most people encounter genital HPV soon after the onset of sexual activity, with the highest risk of infection in the first five to 10 years after sexual activity.

Dr Wain said that for whatever reason, some individuals do not clear their infections, and if these infections are caused by a high-risk variety of HPV, this persistence will lead to activation of oncogenic vital proteins, the loss of cellular control mechanisms and potentially, malignant growths.

“Screening programs based on cytology have had significant impacts on the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer by detecting these potential cancer precursors, but HPV vaccines can primarily prevent the infection.

Advertisement

“These vaccines have shown no therapeutic efficacy for pre-existing infections,” he said.

Advertisement

Dr Wain said excessive promotion of these vaccines for use in women in the 24 to 45 year age group potentially diverts attention away from established methods of cervical cancer prevention based on cervical cytology.

“In the older age group, the vaccine is likely to be of substantially reduced efficacy because of either previous exposure or reduced risk of future exposure,” he said.

The Medical Journal of Australia is a publication of the Australian Medical Association.

Source-MJA

SRM/ga