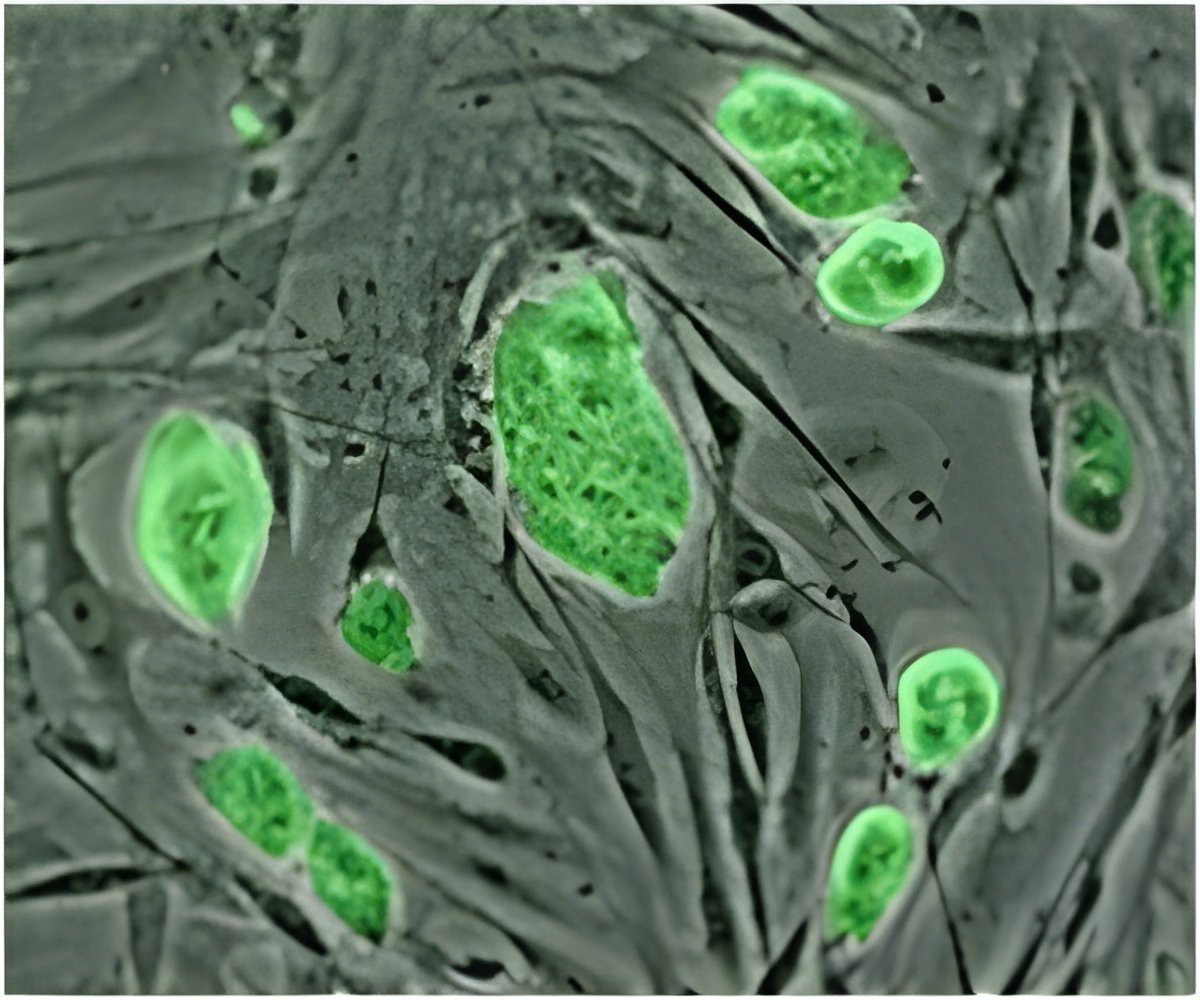

In a recent research, scientists reprogrammed skin cells from patients with rare blood disorders into human induced pluripotent stem cells.

Weiss, with Monica Bessler, M.D., Philip Mason, Ph.D., and Deborah L. French, Ph.D., all of CHOP, led a study on iPSCs and Diamond Blackfan anemia (DBA) published online June 6 in Blood. Another study by Weiss, French and colleagues in the same journal on April 25 focused on iPSCs in juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML).

In DBA, a mutation prevents a patient's bone marrow from producing normal quantities of red blood cells, resulting in severe, sometimes life-threatening anemia. This basic fact makes it difficult for researchers to discern the underlying mechanism of the disease: "It's very difficult to figure out what's wrong, because the bone marrow is nearly empty of these cells," said Bessler, the director of CHOP's Pediatric and Adult Comprehensive Bone Marrow Failure Center.

The study team removed fibroblasts (skin cells) from DBA patients, and in cell cultures, using proteins called transcription factors, reprogrammed the cells into iPSCs. As those iPSCs were stimulated to form blood tissues, like the patient's original mutated cells, they were deficient in producing red blood cells.

However, when the researchers corrected the genetic defect that causes DBA, the iPSCs developed into red blood cells in normal quantities. "This showed that in principle, it's possible to repair a patient's defective cells," said Weiss.

Weiss cautioned that this proof-of-principle finding is an early step, with many further studies to be done to verify if this approach will be safe and effective in clinical use.

Advertisement

Furthermore, the cells offer a renewable, long-lasting model system for testing drug candidates or gene modifications that may offer new treatments, personalized to individual patients.

Advertisement

They then tested the cells with two drugs, each able to inhibit a separate protein known to be highly active in JMML. One drug, an inhibitor of the MEK kinase, reduced the proliferation of cancerous cells in culture. "This provides a rationale for a potential targeted therapy for this specific subtype of JMML," said Weiss.

A stem cell core facility at CHOP, directed by study co-author Deborah French under the auspices of the hospital's Center for Cellular and Molecular Therapeutics, generated the iPSCs lines used in these studies. The facility's goal is to develop and maintain standardized iPSCs lines specific to a variety of rare inherited diseases—not only DBA and JMML, but also dyskeratosis congenita, congenital dyserythropoietic anemia, thrombocytopenia absent radii (TAR), Glanzmann's thrombasthenia and Hermansky- Pudlak syndrome.

A longer-term goal, added Weiss, is for the iPSC lines to provide the raw materials for eventual cell therapies that could be applied to specific genetic disorders. "The more we learn about the molecular details of how these diseases develop, the closer we get to designing precisely targeted tools to benefit patients."

Source-Eurekalert