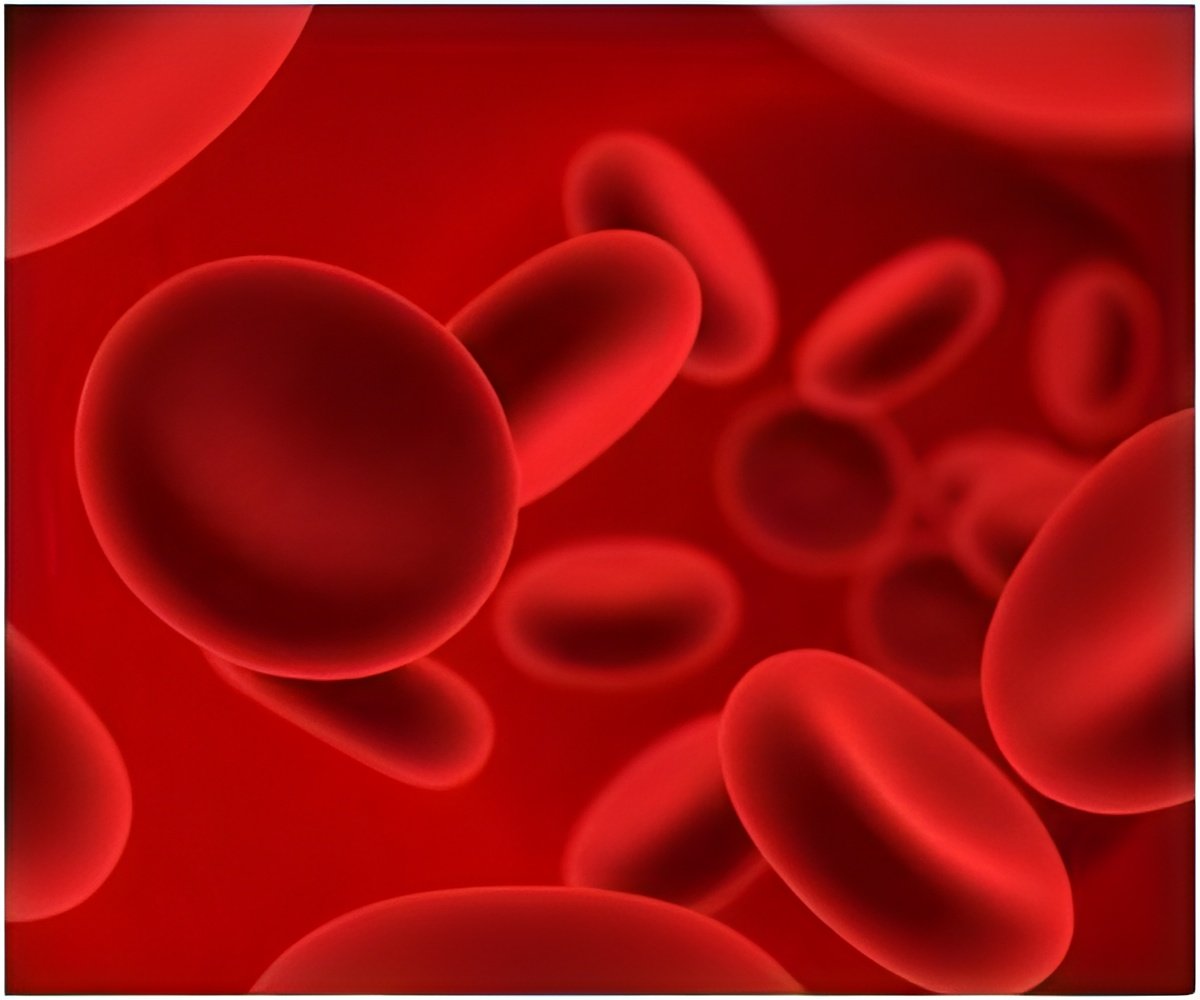

Researchers at the University of Maryland have used a microscopic worm to explain how humans and other organisms safely move iron around in the body.

Using the C. elegans that lives in dirt, the research team lead by Associate Professor Iqbal Hamza identified a protein, called HRG-3 that transports heme.

Heme is known as the iron-containing molecule that creates hemoglobin in blood from the mother's intestine to her developing embryos.

According to the team, the newly identified HRG-3-mediated pathway for transporting heme to developing oocytes, also appears to be an excellent target for stopping the reproduction of hookworms and other parasites that feed on host red blood cell hemoglobin.

"We've known the structure of hemoglobin for a really long time, but we haven't been able to figure out how the heme gets into the globin, or exactly how humans and other living organisms move heme, which like iron is toxic, around and between cells," said Hamza.

"What we've found in our current study is that this protein, which we named HRG-3, takes heme from the worm intestine to the embryos," he explained.

Advertisement

The study has been published in the journal Cell.

Advertisement