Cancer researchers are eying to unlock the cellular-level function of the telomerase enzyme, which is linked to the disease's growth.

The number of times a cell divides is determined by telomeres, protective caps on the ends of chromosomes that indicate cell age. Every time a cell divides, the telomeres shorten. When telomeres shrink to a certain length, the cell either dies or stops dividing. In cancer cells, the enzyme telomerase keeps rebuilding the telomeres, so the cell never receives the cue to stop dividing.

Although telomerase was discovered in 1985, exactly how this enzyme repairs telomeres to enable cancer cells to divide and grow was largely unknown. Until now, researchers didn't know how many telomerase molecules went into action at the telomeres and under what conditions.

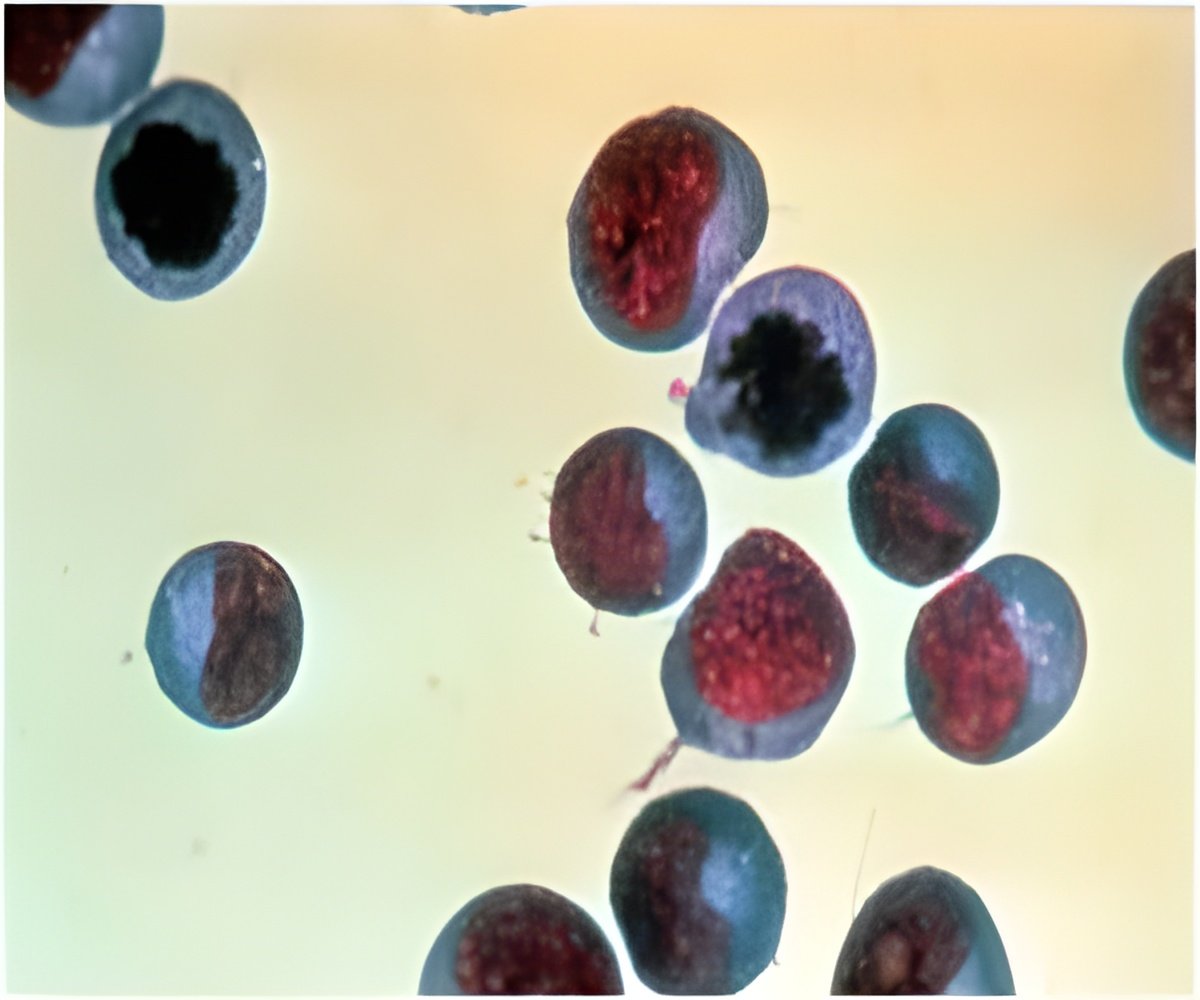

"It's a single molecule under normal cancer growth conditions, but if you shorten telomeres artificially by inhibiting telomerase, now it's more than one molecule acting on the ends of the telomeres," said Dr. Woodring Wright, professor of cell biology and senior author of the study.

When acting as a single molecule at the telomeres, telomerase adds about 60 nucleotide molecules "in one fell swoop to the end of the chromosome," Wright added.

Researchers also discovered that structures in cells called Cajal bodies help process telomerase during chromosome-repair activity. Cajal bodies assemble ribonucleic acid (RNA) within proteins.

Advertisement

The study has been published in Molecular Cell.

Advertisement