Scientists say that some babies diagnosed with and treated for a bone marrow failure disorder, called Diamond Blackfan Anemia, may actually be affected by a very rare anemia syndrome.

The treatment choices are difficult in both syndromes, but getting the diagnosis correct is crucial, said Suneet Agarwal, MD, PhD, a pediatric hematologist/oncologist at Dana-Farber/Boston Children's. "Some patients with Diamond Blackfan will respond to steroids, but there's no reason to give steroids to someone with Pearson syndrome -- and they could make things worse," he said.

Diagnosing Pearson Marrow Pancreas syndrome (PS) is not simple, but a specific laboratory test can spot a characteristic abnormality in the infant's DNA that carries blueprints for making proteins in the cells' energy-producing mitochondria.

The test "should be performed in the initial genetic evaluation of all patients with congenital anemia," said Agarwal, who is also affiliated with the Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research at Boston Children's Hospital.

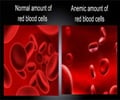

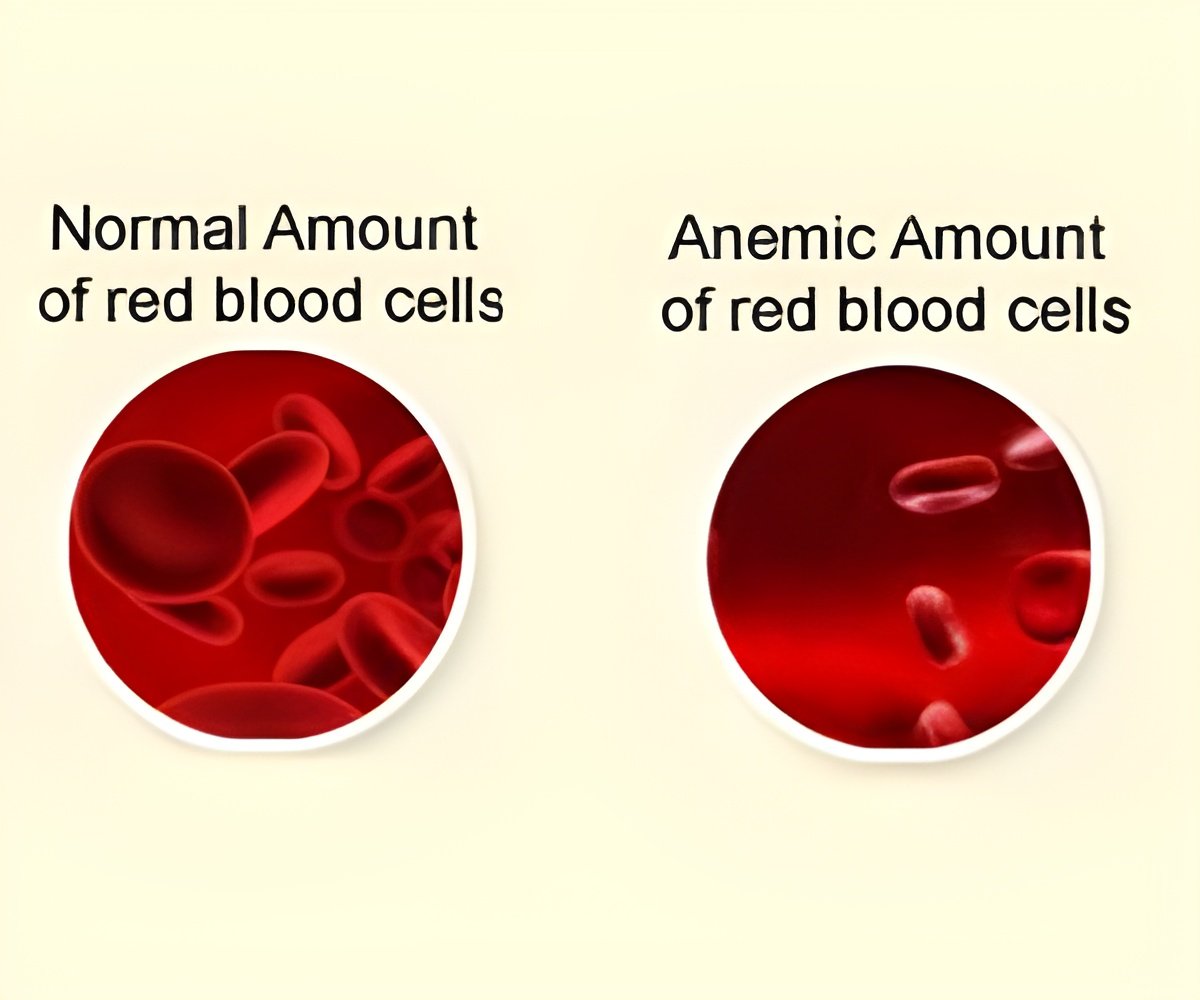

The two disorders are caused by genetic abnormalities that impair production of blood cells by the bone marrow, causing severe anemia usually diagnosed in the first year of life. Diamond Blackfan Anemia affects approximately one in 100,000 infants and can vary widely in its severity. About 50 percent of patients have physical abnormalities affecting different parts of the body.

Because Diamond Blackfan Anemia is typically inherited from parents in an autosomal dominant fashion, with only one parent carrying the abnormal gene, each pregnancy carries a 50 percent risk of resulting in an affected child.

Advertisement

Infants with PS also have anemia and growth defects. They are deficient in pancreatic function and can have muscle and neurologic impairments. Agarwal says it isn't always diagnosed in infancy, because the anemia may not be severe and can even improve without treatment. That's because the patient's cells carry a mixture of normal and mutant mitochondrial DNA. Over time, the proportion of mutant mitochondrial DNA in the blood cells may lessen and the anemia becomes less severe.

"Because patients with Pearson Syndrome can get over their blood defect as young children, and because bone marrow transplantation does not cure the other problems in their bodies, the decision to proceed with transplant is more difficult," he added.

First author of the report is Katelyn E. Gagne of Boston Children's. Others include Mark Fleming, MD, DPhil, of Dana-Farber/Boston Children's; and Hanna Gazda, MD, PhD, of Boston Children's.

The Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research, the Harvard Stem Cell Institute and the Charles H. Hood Foundation funded the study.

The Dana-Farber/Boston Children's Cancer and Blood Disorders Center brings together two internationally known research and teaching institutions that have provided comprehensive care for pediatric oncology and hematology patients since 1947. The Harvard Medical School affiliates share a clinical staff that delivers inpatient care at Boston Children's Hospital and outpatient care at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute's Jimmy Fund Clinic. Dana-Farber/Boston Children's brings the results of its pioneering research and clinical trials to patients' bedsides through five clinical centers: the Blood Disorders Center, the Brain Tumor Center, the Hematologic Malignancies Center, the Solid Tumors Center, and the Stem Cell Transplant Center.

Source-Newswise