Researchers at University of Alberta have identified new ways through which they can utilize caffeine’s lethal effects on cancer cells by testing them out on fruit files.

But given the toxic nature of caffeine at high doses, researchers from the faculties of medicine and dentistry and science instead opted to use it to identify genes and pathways responsible for DNA repair.

"The problem in using caffeine directly is that the levels you would need to completely inhibit the pathway involved in this DNA repair process would kill you," said Shelagh Campbell, co-principal investigator.

"We've come at it from a different angle to find ways to take advantage of this caffeine sensitivity," the researcher noted.

Lead authors Ran Zhuo and Xiao Li, both PhD candidates, found that fruit flies with a mutant gene called melanoma antigen gene, or MAGE, appeared normal when fed a regular diet but died when fed food supplemented with caffeine.

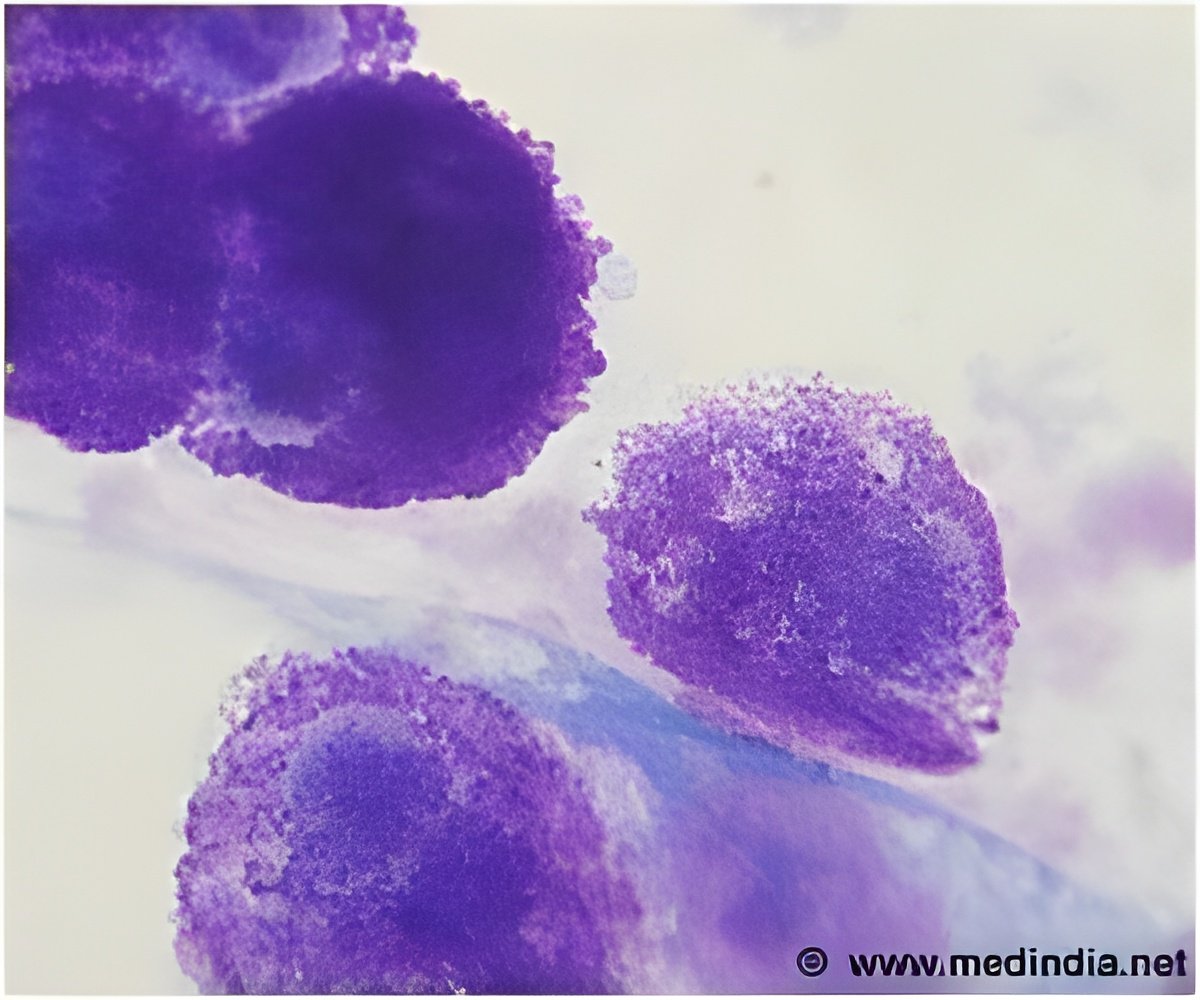

On closer inspection, the researchers found that the mutant flies' cells were super-sensitive to caffeine, with the drug triggering "cell suicide" called apoptosis. Flies fed the caffeine-laden diet developed grossly disfigured eyes.

Advertisement

Co-principal investigator Rachel Wevrick explained that this finding is significant because it means that scientists one day could be able to take advantage of cancer-cell sensitivity to caffeine by developing targeted treatments for cancers with specific genetic changes.

Advertisement

"You need to know which genes and proteins are the really bad actors, how these proteins work and which of them work in a pathway you know something about where you can actually tailor a treatment around that information," she added.

Their results were published in the March issue of the peer-reviewed journal PLOS One.

Source-ANI