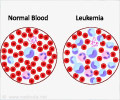

A potential risk of transfusing donated platelets, especially to patients with bone marrow failure syndromes who are subsequently candidates for bone marrow transplantation has been identified.

A potential risk of transfusing donated platelets, especially to patients with bone marrow failure syndromes who are subsequently candidates for bone marrow transplantation has been identified.

The results are online and scheduled for publication in the September 1 issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation.Doctors have noticed a pattern in performing bone marrow transplants as a cure for diseases involving bone marrow failure: more transfusions before a bone marrow transplant correlates with a higher likelihood of rejection, says James Zimring, MD, PhD, assistant professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Emory University School of Medicine.

However, the cause-and-effect relationship between transfusion and bone marrow transplant rejection is unclear. More transfusions may just be needed to treat more severe disease, and more severe underlying disease may cause increased rates of bone marrow transplant rejection, Zimring says.

"Platelets are mostly given to prevent or to stop acute bleeding or hemorrhage. Clearly, none of us would risk a patient bleeding to avoid possible complications for a subsequent bone marrow transplant. Greater understanding of the biology involved is required to modify our transfusion and/or transplantation procedures so as to circumvent the problem," he says.

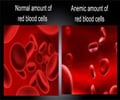

Bone marrow failure syndromes can be inherited or acquired as result of infection or exposure to radiation, insecticides or industrial solvents. Bone marrow failure means the bone marrow can't produce new blood cells, leading to anemia, trouble fighting infections and difficulty controlling bleeding.

To probe for the causes of bone marrow transplant rejection after transfusions, Zimring, graduate student Seema Patel and co-workers established a model system in mice. The system was designed to simulate transplants for bone marrow failure syndromes and do not apply to transplants carried out to treat cancer, which destroy more of the immune system beforehand.

Advertisement

Platelets are already processed to remove white blood cells, with the aim of reducing the risk of immune-related problems. In addition, blood banks already test for antibodies against proteins encoded by MHC genes. In humans, MHC genes are known as HLA (human leukocyte antigen).

Advertisement

Ultimately, modification of the transfused platelets or matching for minor antigens on donated platelets may remedy the problem, he says. A careful human clinical study would be required to establish if the same mechanisms occur in humans.

A related paper by Zimring and his colleagues describing the effects of pre-transplant transfusions of red blood cells in mice was recently published in the journal Blood.

Source-Eurekalert

RAS