With major advances in genetics and exponential growth of knowledge about the immune system, scientists hope important discoveries to treat autoimmune diseases are within reach.

Autoimmune diseases may be among the most mysterious of ailments afflicting mankind, but as the humankind gets to know better the mechanism of the body, it might have begun to crack the mystery of it all.

"The capacity to explore the human genome has reached the worker bee," says John Harley of the Arthritis and Immunology Research Program at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation in Oklahoma City. "It has filtered down far enough that we now have the capacity to do experiments we only dreamed of 10 years ago."Now, he says, "the whole range of human disease is going to be studied using this approach and will produce new clues that will be utterly transforming in our ability to manipulate the fundamental disease process."

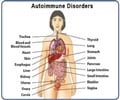

Disorders of the immune system can be debilitating and expensive, and are likely to be much more common than previously realized. But just how many people have them is not known, because such diseases are not tracked. The National Institutes of Health estimated in a 2005 report that 5% to 8% of Americans, up to 23.5 million, have one or more autoimmune diseases, which occur when the immune system launches an attack on healthy cells within its own body.

In the current issue of the Journal of Clinical Immunology, researchers estimate, based on a random telephone survey, that another group of immune disorders called primary immune deficiency diseases may afflict as many as one in 1,200. In these diseases, caused by an inborn genetic defect, the body can't mount an effective immune response to infection.

"Almost every autoimmune disease, with the exception of rheumatoid arthritis, seems to be going up," says immunologist Noel Rose, director of the Johns Hopkins Autoimmune Diseases Research Center. But whether that's because of an increase in disease or better recognition of cases is not certain.

The immune system is nature's built-in security force. When working properly, it detects an incoming attack upon the body, whether by viruses or other organisms, and mounts a protective response. When the invader is vanquished, it calls off the troops. But when that system malfunctions, the body's internal security force can lay down its arms or even turn on itself.

Advertisement

"When you have type 1 diabetes, there's a relatively clear boundary between when you have it and when you don't," says Josiah Wedgwood, chairman of the Autoimmune Diseases Coordinating Committee at the National Institutes of Health. "With most of the other autoimmune diseases, there isn't a clear boundary like that. There's a problem called an ascertainment bias: You identify the sickest patients always, but like an iceberg, are you only looking at the surface? And what's beneath?" Often, patients go from doctor to doctor, desperate for a diagnosis.

Advertisement

For Kylynn Welsh, it took more than 12 years. The teenager is missing a blood protein needed to stop the immune response. If she gets a cut or a bump or if she catches a cold, her body's immune system swings into gear, sending white blood cells and fluids to the affected area, causing inflammation and swelling. But her body can't turn off the response. "It's like driving a car without a brake pedal," Wedgwood says.

As a child, Kylynn would have unexplained bouts of swelling, says her mother, Sandra Welsh. After gym one day, her legs swelled painfully. Sometimes her belly would puff up, causing agonizing pain. "One time, her face was so distorted that her scalp swelled down over her eyes and she couldn't open her eyes," Welsh says.

After four hospitalizations and dozens of medical evaluations, doctors pinpointed the disease as hereditary angioedema, a disorder that is usually inherited but can result from a genetic mutation before birth. No one in her family has had it, Welsh says. "I said, 'OK, now I know what devil I'm playing with.' "

In her most recent hospitalization, Kylynn went to Cooper Medical Center in Camden, New Jersey to have dental work done, which requires plasma infusions because of her immune system disease. But "her throat started to bother her the day we were coming in for the procedure, and before we could get a (hospital) bracelet on her arm, her throat closed," her mother says.

It was a moment of panic. "She was dying in front of me," Welsh says. A critical-care doctor recognized the signs of distress and said, " 'Let's go, let's go,' " Welsh says. He inserted a fiber-optic scope through Kylynn's nose and throat to see where the swelling was, so he could insert a breathing tube.

In May, Reagan Williams, who turns 10 next Sunday, complained to her mother about being frequently thirsty and needing to get up at night to go to the bathroom. She was tired and grumpy and was losing weight. "I was thinking those are classic diabetes symptoms," says her mother, Teresa Osborne of Westborough, Mass. But "I didn't know they were symptoms that needed immediate attention."

It wasn't until Reagan felt sick to her stomach after being out to dinner that her symptoms became truly alarming. She drank juice before bed and in the morning was "lethargic and very unfocused." When she was no better the next day, Osborne took her to the emergency room. There, she was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, a disease in which the immune system destroys insulin-producing cells.

Reagan was in a state of diabetic ketoacidosis, a dangerous condition caused by extremely high blood sugar. After 31/2 days in the hospital, she was able to go home to begin life with diabetes. She takes four shots of insulin a day and tests her blood sugar six times a day.

She is back on her feet now, enjoying her first days in fourth grade. The 18-year-old Welsh should has also been discharged from the hospital and will soon be starting college, her mother says.

Such dramatic recoveries should make the medical community ever more confident in tackling such diseases.

Iimmune system disorders often cluster in families and within an individual, says Virginia Ladd, president of the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association. "Once you have one, you have others. Some patients say if you live long enough, you can collect them."

Paul Strumph, chief medical officer of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, agrees. People with type 1 diabetes are more likely to have other autoimmune disorders, such as thyroid disease or celiac disease, an intestinal disorder, he says. "The factors that make people have type 1 diabetes, whatever they are, have implications for other autoimmune diseases."

Scientists believe autoimmune diseases are caused by a genetic predisposition activated by some environmental exposure.

"We don't understand all the factors influencing the immune system, but there has been an explosion in interest," Strumph says. Possibilities include exposure to new germs, a result of international travel and commerce, a deficiency in vitamin D, an excess of cleanliness that stunts immune system development, even obesity.

But he and others who specialize in immune disorders are optimistic. The development of huge public databases about human genetics and technologies that allow scientists to test thousands of samples in a day will lead to new drugs tailored to a person's genetic makeup, new ways to predict susceptibility to disease and possibly ways to prevent them.

It may be a decade or more before "the discoveries being made today are fully realized in patients," says Harley of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation. But the advances in research capability of the past several years are like "the difference between horseback and a Learjet," he says. "That's the kind of transition we're undergoing at the moment. The country should have an appreciation for this and celebrate it. Life is extremely complicated, and the fact that we understand any of it is a miracle."

Source-Medindia

GPL/J