A new software devised by scientists could enable a common laboratory device to virtually separate a whole-blood sample into its different cell types and detect important gene-activity changes

A new software devised by scientists could enable a common laboratory device to virtually separate a whole-blood sample into its different cell types and detect medically important gene-activity changes specific to any one of those cell types.

Developed by scientists at the Stanford University School of Medicine, the new technique could successfully pinpoint changes in one cell type that flagged the likelihood of kidney-transplant recipients rejecting their new organs.Without the software, these gene-activity flags would have gone unnoticed.

According to the authors, the use of the new algorithm may have applications beyond kidney rejection, allowing doctors to better identify the onset of cancers, genetic disorders and a variety of other problems.

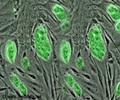

The lab device, called a microarray, is a standard research tool, but it was not used to derive such medically useful information from whole-blood samples, until now.

Part of the problem is that the information is obscured by the whole-blood samples' complex, multiple-component composition.

"Drawing blood is one of the most common diagnostic tests in clinical practice. We'd love to be able to use microarrays to find changes in the blood that indicate trouble somewhere in the body. But distinguishing one type of cell from another can be critical to doing that," Nature quoted one of the investigators, Dr. Atul Butte, as saying.

Advertisement

Still, whole blood poses a complication when used as a sample in microarray analyses.

Advertisement

Thus, the investigators devised an algorithm - in this case, a very large number of fairly simple equations.

To test the algorithm's accuracy, the researchers obtained whole blood samples from 24 pediatric kidney-transplant patients.

Fifteen of the 24 patients were experiencing symptoms of acute transplant rejection, while nine were in stable condition.

Because complete blood counts had been routinely performed on these patients, the frequencies within each sample of five important blood-cell types - monocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils, basophils and eosinophils - were known.

Analyzing patients' whole blood samples via microarrays without resorting to the new algorithm, the investigators couldn't distinguish any gene-expression pattern differences between the two patient groups.

But when they used the new algorithm, they found hundreds of differences in gene expression.

Those differences could be used to tell which patients were rejecting their transplants and which were not.

In addition, this method let the researchers see that these changes were largely confined to one particular cell type: the monocytes.

Only the new virtual-separation technique made fingering this cellular culprit possible.

The study has been published in Nature Methods.

Source-ANI

RAS