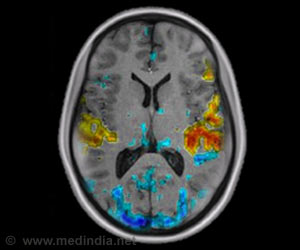

Scientists have discovered that when the right supramarginal gyrus doesn't function properly or when we have to make particularly quick decisions, our empathy is severely limited.

While participant 1, for example, could see a picture of maggots and feel slime with her hand, participant 2 saw a picture of a puppy and could feel soft, fleecy fur on her skin.

The two participants were then asked to evaluate either their own emotions or those of their partners. As long as both participants were exposed to the same type of positive or negative stimuli, they found it easy to assess their partner's emotions. The participant who was confronted with a stinkbug could easily imagine how unpleasant the sight and feeling of a spider must be for her partner.

Differences only arose during the test runs in which one partner was confronted with pleasant stimuli and the other with unpleasant ones. Their capacity for empathy suddenly plummeted.

The participants' own emotions distorted their assessment of the other person's feelings. The participants who were feeling good themselves assessed their partners' negative experiences as less severe than they actually were. In contrast, those who had just had an unpleasant experience assessed their partners' good experiences less positively.

It was found that the right supramarginal gyrus ensures that we can decouple our perception of ourselves from that of others.

Advertisement