The structure of a very complicated and important brain protein, which is shaped like a temple has been unraveled by researchers.

The structure of a very complicated and important brain protein, which is shaped like a temple has been unraveled by researchers. This is an accomplishment that could trigger the development of new treatments for a wealth of neurological disorders.

Eric Gouaux and his colleagues undertook the difficult task of mapping the structure of a glutamate receptor, a protein that mediates signalling between neurons in the brain and elsewhere in the nervous system.The receptor is also thought to be crucial to processes such as memory and learning.

The resulting picture "tells us things about the organization of the receptor that were just completely unanticipated" said Gouaux, a protein crystallographer at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland.

The researchers studied a rat glutamate receptor known as GluA2.

They grew a crystal of many such proteins, then exposed this to a beam of X-rays.

After watching how X-rays scattered from the crystal, they could produce an atomic-level picture of a single protein.

Advertisement

Knowing the shape of an intact glutamate receptor will not only allow scientists to better understand how it works, but should also help those working to develop therapies for conditions in which something goes awry with the system, such as epilepsy and Alzheimer's disease.

Advertisement

"If you know what the lock looks like then you can better design a key. If you don't know you're at a loss," Nature quoted Gouaux as saying.

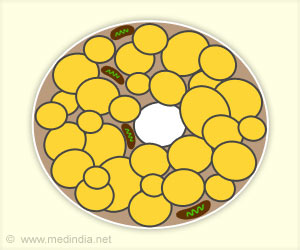

The GluA2 receptor is shaped like a capital letter Y, and has three main parts. At the top are two prongs, which can enable modification of the receptor.

Below this is the area where glutamate binds, triggering the opening of the ion channel. And at the bottom is the channel itself, shaped, "like a Mayan temple", said the authors.

The receptor comprises four subunits, which are chemically identical but, surprisingly, are folded differently (see picture).

"The completely astonishing thing was that two subunits are completely different from the other two. That difference was totally unanticipated," said Gouaux.

The study will be published in Nature.

Source-ANI

RAS