A liver cancer research led by an oncologist of Indian origin has reported the discovery of both “cancer stem cells” and normal stem cells in the liver.

A study led by an Indian oncologist has reported the novel discovery of both “cancer stem cells” and normal stem cells in the liver.

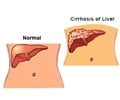

The authors say that comparison between their genetic “signatures” can lead to the development of an experimental drug, thus aiding the treatment of liver cancer.It has long been believed that up to 40 percent of liver cancer is caused by gone wild, master cells in the organ that have lost all growth control. However, until now the scientists were unable to find any kind of good or bad cancer cells in the liver.

The results of this study by Lopa Mishra, M.D., Director of Cancer Genetics in the Department of Surgery at Georgetown University and the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, have indicated that use of the agent, a stat3 inhibitor, significantly inhibited liver cancers in human cancer cell lines and mice.

“After locating the cancer stem cells that help control development of these tumours, we were able to find a potential vulnerability that might form the basis of a new treatment for this disease - which is greatly needed,” said Mishra.

She said that liver (hepatocellular) cancer is one of the most lethal and prevalent cancers in the world and 5-year survival in the disease is less than 5 percent.

The results of the study come through decades of research in Mishra’s laboratory into the genetic pathways important to development of liver cancer.

Advertisement

Mishra said that the TGF-? family of proteins is responsible for keeping stem cells in an undifferentiated state, but when needed it also directs the development of these cells into specialized cells. She added that they are also powerful suppressors of cancer development.

Advertisement

Though it was clear by these studies that stem cells gone wild were key to liver cancer development, it was not possible for anyone to find such cancer stem cells, or any stem cells, in liver tissue in order to test the theory.

But it was suggested by Georgetown transplant surgeon Lynt Johnson, M.D., that they should try finding stem cells in donor liver tissue that had been newly transplanted into patients with a failing organ. He reasoned that stem cells in this tissue would be particularly active because they would be busy creating new liver cells.

This made the researchers to take biopsies from six surgery patients of liver tissue up to four months past transplantation were studied. And it was in this regenerating tissue that normal stem cells were finally found. Thse cells were rare—two to four cells per 30,000-50,000 cells, but they expressed all the proteins known to be associated with stem cells, such as Stat3, Oct4, Nanog, ELF, and receptor for the TGF-? protein.

“These cells were working really hard, expressing all of these proteins in abundance. In our staining tests they looked like stars, surrounded by shells of cells that were also expressing TGF-? in order to make new liver cells,” said Mishra.

Later, the researchers examined tissue from 10 patients with liver cancer using the same antibody test that located the stem cells in the regenerating livers , to look for cancer stem cells.

“We found that all of these stem cells had lost TGF-? Without the brakes that TGF-? puts on cancer, the stem cells had turned into bad guys,” she said.

The scientists turned to mouse models of liver cancer to see what would happen if they took out the “stemness” in the cancer stem cells and found that only 1 in 40 mice bred without a stat3 gene developed liver cancer. “But with the stat3 gene intact, 70 percent of mice developed the cancer,” Mishra said.

In the final stage of the study, the researchers are treating mice with liver cancer that had normal stat3 gene but are missing TGF-? with an experimental stat3 inhibitor drug in development by the National Cancer Institute, an agent that would shut down stat3.

Source-ANI

SPH/K