Changes that occur during the aging process make brain cells more susceptible to disease-causing mutations that can have adverse effects on elderly.

‘Slowing aging process helps prevent the loss of dopamine-producing cells in the brain and decreases the formation of protein clumps, which are hallmark features of Parkinson’s disease.’

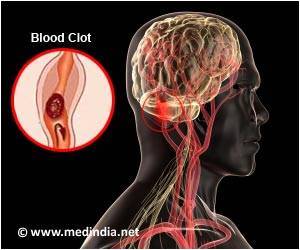

"It is unknown why symptoms take many decades to develop when inherited mutations that cause the disease are present from birth," said Jeremy Van Raamsdonk, a VARI assistant professor and the study's senior author. "Aging is the greatest risk factor for developing Parkinson's. We believe changes that occur during the aging process make brain cells more susceptible to disease-causing mutations that don't cause issues in younger people." In the brain, Parkinson's is marked by the dysfunction and death of the nerve cells that produce dopamine--a chemical that plays a key role in many important functions, including motor control. Clumps of a protein called alpha-synuclein also are found in brain cells of most people with Parkinson's, although scientists are still trying to pin down their exact role.

As part of their search for ways to prevent the disease, Van Raamsdonk's team delayed the aging process in genetic models of Parkinson's disease. They demonstrated that slower aging imparts protection against the loss of dopamine-producing cells in the brain and decreases the formation of alpha-synuclein clumps; both hallmark features of Parkinson's.

"This work suggests that slowing aging can have protective effects on the brain cells that otherwise may become damaged in Parkinson's," Van Raamsdonk said. "Our goal is to translate this knowledge into therapies that slow, stop or reverse disease progression."

Slowing Aging, Preserving Brain Cell Function

Advertisement

Worm models of Parkinson's disease that expressed either a mutated LRRK2 gene or a mutated alpha-synuclein gene--both of which cause Parkinson's--were crossed with a long-lived strain of the worm to create two new strains with longer lifespans.

Advertisement

From Worms to People

The long-lived strain of C. elegans Van Raamsdonk used for the crosses has a mutation in daf-2, a gene that encodes for a member of the insulin and IGF1 signaling pathways. Genes in these pathways are also associated with longevity in humans; however, therapies that affect the pathways may need to be carefully controlled to mitigate potential side effects. As such, Van Raamsdonk plans to investigate this link in other Parkinson's disease models and to search for additional pathways involved in longevity that have a lower risk of side effects, while still effectively slowing or preventing disease onset. The study was published online In Parkinson's Disease, a new journal from Nature Publishing Group.

Source-Eurekalert