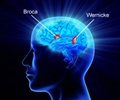

Individuals with damage to the front part of the brain may have choppy or non-fluent speech. However, they can typically understand what people say fairly well.

‘The speech-language pathologist (SLP) evaluates the individual with a variety tools to determine the type and severity of aphasia.’

The ability of the residual language network to rebuild itself (a characteristic called structural plasticity) is directly related to how much benefit a patient receives from speech therapy, report investigators at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in an article published online June 19, 2017 by Annals of Neurology. Their study also supports the dual-stream language model, which holds that ventral brain networks are associated with semantic skills and dorsal networks with phonemic skills. "Producing speech is a two-step process - first selecting the correct word using semantic associations and, then, pronouncing it phonetically," explains lead author Emilie T. McKinnon, an M.D., PhD candidate in MUSC's Department of Neurology. "The current theory is that different parts of the brain house these two processes. If that's the case, these areas have to communicate with each other to produce language. So, the question is, when one of those regions is damaged, how is that connection restored? We looked at the microstructure of one of those connections to try to see what happens when language processing improves."

The team tested eight aphasia patients, all of whom had had a single stroke at least one year prior that affected the ILF region. Participants were tested for confrontational naming ability one week before and one week after receiving a three-week course of intensive speech therapy. In addition, participants underwent four magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sessions - two before speech therapy and two after.

A novel aspect of the study was how the MRIs were conducted and assessed. The investigators leveraged recent advancements in diffusion-weighted imaging and image analysis, providing greater sensitivity to microstructural white matter changes and revealing previously hidden differences.

"Diffusion-weighted imaging has been around a long time and it's useful for mapping and studying brain networks, but the commonly used analysis techniques can be improved upon," explains McKinnon. "We used diffusion kurtosis imaging and kurtosis-based tractography to calculate how water diffuses in the brain and identify areas of high resistance. Where water diffuses unimpeded, kurtosis is near zero. The more barriers it meets, the higher the kurtosis. So, it's a measure of how complex the environment is. We used this strategy because we could get so much more information and it only required adjusting the MRI settings and adding about five minutes of scanner time."

Advertisement

Furthermore, when the research team applied more conventional measurement strategies, the results were not statistically significant -- suggesting that traditional methods may be less sensitive to the microstructural changes associated with recovery.

The finding that kurtosis improvements are related to structural improvements is an important clue to how aphasia recovery occurs. "We saw that people got better because their brain network got structurally stronger," says Bonilha. "The residual connections got stronger in an area where semantic knowledge is integrated. Phonemics weren't related to these changes."

McKinnon hopes that the findings will ultimately contribute to therapeutic decision-making. "The goal is to be able to look at an MRI and see where the patient's residual strength is," she says. "If we see that the ventral area is really weak, but the phonemics network is damaged beyond repair, we could recommend semantically oriented therapies."

Additionally, this strategy may be useful in other conditions. For example, other brain functions such as motor control are also damaged by stroke. "The same microstructural changes would have to happen to recover use of a hand," says McKinnon. "So, you could look for the same results with post-stroke motor rehabilitation and, maybe, beyond stroke, in cases of neurodegeneration or brain damage, such as traumatic brain injury. If we can find a relationship between the network structure and function, then we could use this technique to assess recovery potential and progress."

Source-Eurekalert