Radiation can temporarily shrink glioblastoma, which is one of the most deadly human brain cancers

Radiation can temporarily shrink glioblastoma, which is one of the most deadly human brain cancers, but they nearly always recur within weeks or months and few patients survive longer than two years after diagnosis.

Now scientists at the Stanford University School of Medicine studying the tumor in mice have found a way to stop the cancer cells from growing back after radiation by blocking its access to oxygen and nutrients. The discovery happened when the researchers realized that irradiated tumors turn to a little-known, secondary pathway to generate the blood vessels necessary for regrowth."Under normal circumstances, this pathway is not important for growth of most tumors," said Martin Brown, PhD, professor of radiation oncology. "What we hadn't realized until recently is that radiation meant to kill the cancer cells also destroys the existing blood vessels that nourish the tumor. As a result, it has to rely on a backup blood delivery pathway." Although the researchers focused their study on glioblastoma, other tumors use a similar mechanism to evade radiotherapy.

Brown and his colleagues used a small molecule called AMD3100 to block this secondary tumor-growth process in the mice. Because AMD3100 has already been clinically approved for a different use in humans, it is possible that the researchers may be able to move relatively quickly into human trials. Still, the researchers caution that routine therapeutic use of AMD3100 or any other similarly acting molecule for glioblastoma is likely still years away.

Brown is the senior author of the paper, which will be published online Feb. 22 in the Journal of Clinical Investigation. Research associate Mitomu Kioi, PhD, is the paper's first author. Neurosurgery professor Griffith Harsh, MD, is a co-author. Brown and Harsh are also members of Stanford's Cancer Center.

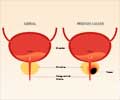

To understand the research, it's necessary to know a bit about how blood vessels form. Most commonly, tumors co-opt existing nearby blood supplies by inducing them to sprout new blood vessels to infiltrate the tumor and nourish the dividing cancer cells — a process called angiogenesis. However, it's also possible to recruit cells from the bone marrow to form new blood vessels where none existed before. This is called vasculogenesis, and is the process blocked by AMD3100.

Earlier research by Brown and others suggested that the heavy doses of radiation used to treat many types of cancers also kills the cells lining the blood vessels in and around the tumor. This means that it can no longer rely on angiogenesis from existing vessels to keep supplied with oxygen and nutrients. Brown hypothesized that instead the tumor recruits the bone-marrow-derived cells, or BMDCs, to form brand-new vessels to keep it from starving. Blocking this pathway, he thought, might be the final blow to the irradiated tumor.

Advertisement

As predicted, irradiating the tumors caused the existing blood vessel cells to die and the tumors to become hypoxic, or starved of oxygen. In response, the tumors begin to express a molecule called hypoxic-inducible factor 1. HIF-1 starts a cascade of events that cause BMDCs to flood the tumor and initiate vasculogenesis. Blocking HIF-1 activity stopped the recruitment of BMDCs and prevented irradiated tumors from recurring throughout the 100-day study period.

Advertisement

Brown and his colleagues tried other ways to inhibit HIF-1-induced vasculogenesis. They knew that AMD3100 interferes with the interaction of two other proteins important in recruiting the bone-marrow-derived cells — one secreted by hypoxic tissue in response to HIF-1, and another found on the surface of the BMDCs. The two proteins lock together to encourage the cells to stay put. In fact, AMD3100 is used in bone marrow transplants to disrupt this interaction and ensure that bone marrow stem cells leave the marrow and enter the blood stream.

The researchers found that giving the mice a continuous infusion of AMD3100, as well as using antibodies against one of the two proteins, also prevented tumor recurrence in the mice. Finally, they confirmed that glioblastoma tissue from 12 human patients who had undergone radiation therapy contained significantly higher levels of bone-marrow-derived cells than did samples from the same patients obtained prior to radiation.

"I think the next step is to test this clinically in humans," said Brown.

Source-Eurekalert

RAS