The structure down to the atomic level of a virus that causes juvenile diarrhea have been defined by Rice University researchers.

Tao's Rice lab specializes in gleaning fine details of viral structures through X-ray crystallography and computer analysis of the complex molecules, ultimately pinpointing the location of every atom. That helps researchers see microscopic features on a virus, like the spot that allows it to bind to a cell or sites that are recognized by neutralization antibodies.

Among four small RNA viruses that typically infect people and animals, Tao said, astrovirus was the only one whose atomic structure was not yet known. First visualized through electron microscopy in 1975, it became clear in subsequent studies that the virus played a role in juvenile -- and sometimes adult -- outbreaks of diarrhea, as the second leading cause after rotavirus. Passed orally, most often through fecal matter, the illness is more inconvenient than dangerous, but if left untreated, children can become dehydrated.

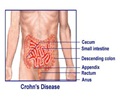

The virus works its foul magic in humans' lower intestines, but to get there it has to run a gauntlet through the digestive tract and avoid proteases, part of the human immune system whose job is to destroy it. (Though one, trypsin, actually plays a role in activating astrovirus, she said.) When the astrovirus finds a target and viral RNA is let loose inside human cells, virus replication starts. If the host's immune system does not do a good enough job in removing the viruses, the malady will run its uncomfortable course in a couple of days.

Astrovirus bears a strong resemblance to the virus that causes hepatitis E (HEV). Tao, an associate professor of biochemistry and cell biology, said she decided to investigate astrovirus after completing a similar study of HEV two years ago. "I was thinking there's some connection between those viruses," she said. "Based on that assumption, we started to make constructs to see if we could produce, to start with, the surface spike on the viral capsid."

Source-Eurekalert