Researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital have identified how dendritic cells in the intestine play an important role in suppressing inflammation.

"In the circuitry we uncovered, mucosal dendritic cells interact with specialized capillaries that allow antigens to move from the blood into intestinal tissues," explains Hans-Christian Reinecker, MD, of the Center for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in the MGH Gastrointestinal Unit, corresponding author of the report released online in the journal Immunity. "Within these dendritic cells, antigens from the blood mix with food and microbial antigens absorbed by the intestine. We were suprised to find that, even before the antigens are carried to the lymph nodes, some are directly processed by intestinal dendritic cells to induce production of a type of T cell that controls intestinal inflammation."

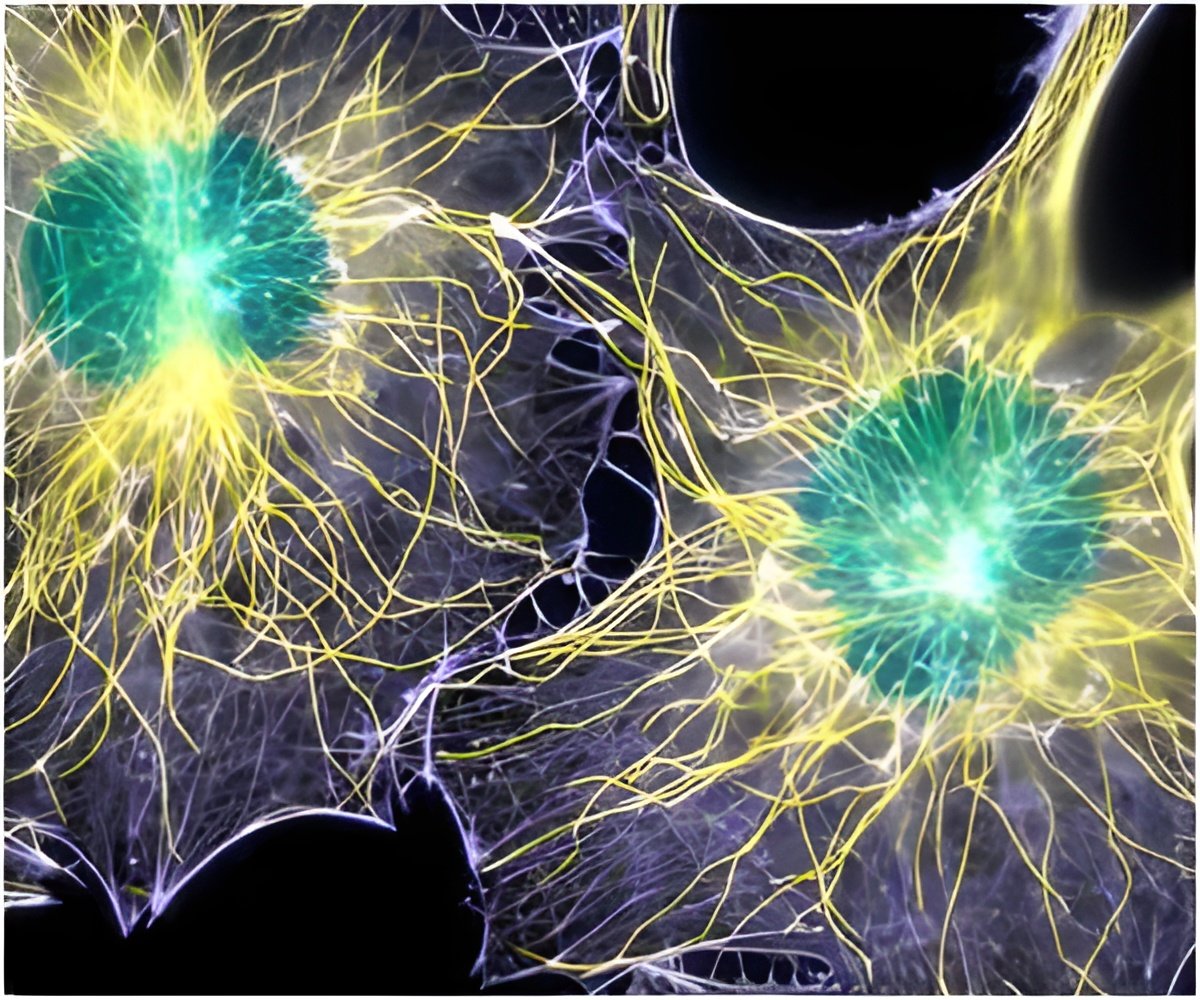

It had been believed that dendritic cells found in the mucosal lining of the small intestine primarily monitored intestinal contents, both to suppress inflammatory reactions against food and to protect against invading pathogens. Nutrients are absorbed into the bloodstream through small pores in intestinal capillaries, but whether those pores allowed dendritic cells in adjacent intestinal tissue to recognize antigens in the blood was not known. Noting that the position within the intestinal lining of a subset of dendritic cells brings them into contact with both the bloodstream and with compounds absorbed from the intestine, Reinecker's team investigated whether those cells collected antigens from both sources.

Experiments in mice confirmed that these dendritic cells, which carry a receptor called CX3CR1, collect and process both circulating and intestinal antigens, inducing production of a type of CD8 T cell that can help induce tolerance to antigens in food. Previously, the source of those intestinal T cells – which differ from the cytotoxic CD8 T cells that kill virally-infected and other damaged cells – and their function were unknown. Further experiments by the MGH team showed that these intestinal CD8 T cells secreted proteins that suppressed the activation of CD4 T cells, preventing intestinal inflammation.

Based on these results, the researchers propose that CX3CR1 dendritic cells in the intestinal lining are a central immune system component for surveillance of both foreign antigens consumed in food and circulating "self" antigens. Since CX3CR1 dendritic cells set off a process leading to suppression of inflammation, disturbance of their function could generate the inappropriate immune response to "self" cells or tissues that characterizes chronic inflammatory and autoimmune disorders.

"When dendritic cells process information about microbes within the intestine, they induce production of both T cells that specifically target those pathogens and regulatory T cells that control the immune response," he adds. "Disruption of the balance between those two types of T cells could lead to inflammatory bowel disorders such as Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Failure to control T cell activation in the intestine also could lead to food allergies and celiac disease; so this regulatory circuit that we have uncovered establishes the small intestinal immune system as a site that could have a major impact on the immune response throughout the body."

Advertisement

Source-Eurekalert