A Montana State University scientist says that bile secretions in the intestine send signals to disease causing gut bacteria enabling them to change their behaviour

A Montana State University scientist says that bile secretions in the intestine send signals to disease causing gut bacteria enabling them to change their behaviour to extend their chances of survival.

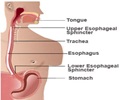

The findings by Steve Hamner and colleagues could allow us to better protect food from contamination by these harmful bacteria, as well as understand how they manage to cause disease.Bile is secreted into the small intestine and exerts an antibacterial effect by disrupting bacterial membranes and damaging bacterial DNA, said the study.

While bile is a human defense mechanism, the researchers found that some bacteria such as Escherichia coli O157:H7 -- an important food-borne pathogen known as E. coli-have evolved to use the signal to their advantage.

These bacteria use the presence of bile as a signal to tell them that they are in the intestine, which allows them to adapt and prepare to cause disease.

They found that bile causes the bacteria to switch on genes needed to increase iron uptake.

"This is useful in iron-scarce environments-such as the small intestine -- as iron is an essential nutrient for bacterial growth. By increasing its chances of absorbing iron, the bacterium is maximizing its survival chances," explained Hamner.

Advertisement

"We found that bile causes the bacteria to turn off genes that promote tight attachment to host cells. Bile may effectively prevent these bacteria from latching onto the epithelial cells that line the small intestine," suggested Hamner.

Advertisement

"The reduced concentration of bile in the large intestine may then be a signal for the bacteria to switch on their ability to attach to epithelial cells and to prepare to secrete toxins," said Hamner.

Studying the conditions that make these bacteria more likely to attach themselves to cells could help reduce outbreaks of food poisoning.

"By learning how the bacteria attach to food surfaces such as spinach leaves or to host tissues such as the lining of the intestine, we hope to better be able to protect food sources from contamination by these bacteria. Studying how these bacteria interact with hosts such as humans or cows could teach us how to interfere with the way that these bacteria cause disease," said Hamner.

The study was presented at the Society for General Microbiology during its spring meeting in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Source-ANI

RAS