A new study from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine has shed light on how chemotherapy drugs slow cancer growth.

A new study from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine has shed light on how chemotherapy drugs slow cancer growth.

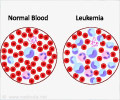

Chemotherapeutics such as doxorubicin (Adriamycin), daunorubicin, epirubicin, idarubicin have been used for four decades to treat many types of cancer, including leukemia, lymphoma, sarcomas and carcinomas.The new research led by Gregg L. Semenza, M.D., Ph.D., director of the vascular program at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Cell Engineering and a member of the McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine has revealed how it works and what players are involved, which could help shape future clinical trials for patients with certain types of cancers.

The researchers know that hypoxia-inducible factor, or HIF-1, protein helps cells survive under low-oxygen conditions. It turns on genes that grow new blood vessels to help oxygen-starved cells, like those found in fast-growing solid tumours, survive.

During the study, the team tested more than 3,000 already FDA-approved drugs for their ability to stop HIF-1 activity.

Then with the help of modified liver cancer cells growing in low oxygen, the team treated cells with each of the drugs and examined whether it could stop HIF-1 from turning on genes.

They found that one drug-daunorubicin-reduced HIF-1's gene-activating ability by more than 99 percent.

Advertisement

To turn on genes, HIF-1 must bind to DNA. So the research team looked at drug-treated and untreated cells and compared regions of DNA known to be bound by HIF-1.

Advertisement

"We know that this class of drug prefers to bind to DNA sequences that are similar to the DNA sequence bound by HIF-1, but this is the first direct evidence that anthracyclines prevent HIF-1 from binding to and turning on target genes," said Semenza.

For further analysis, the team grew tumors in mice from human prostate cancer cells. They treated these mice with daunorubicin, doxorubicin or saline once a day for five days and measured tumor size.

They found that tumors in saline-treated mice nearly doubled in size in that time, whereas tumors in the drug-treated mice stayed the same size or became smaller.

When the team examined the tumors from drug-treated mice, they found that the number of blood vessels was dramatically reduced compared to mice treated with saline.

Moreover, the genes that HIF-1 turns on to drive blood vessel formation were turned off in tumours from the drug-treated mice.

The study appears in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Early Edition.

Source-ANI

SRM