A new and key molecular mechanism within macrophages -- infection-fighting cells of the innate immune system -- that determines whether and how well the cells can be trained has been discovered.

‘The human body's immune cells naturally fight off viral and bacterial microbes and other invaders, but they can also be reprogrammed or "trained" to respond even more aggressively and potently to such threats, say scientists who have discovered the fundamental rule underlying this process in a particular class of cells.’

"Like a soldier or an athlete, innate immune cells can be trained by past experiences to become better at fighting infections," said lead author Quen Cheng, Assistant Clinical Professor of infectious diseases at the UCLA's David Geffen School of Medicine However, he noted, the researchers had previously observed that some experiences seemed to be better than others for immune training.

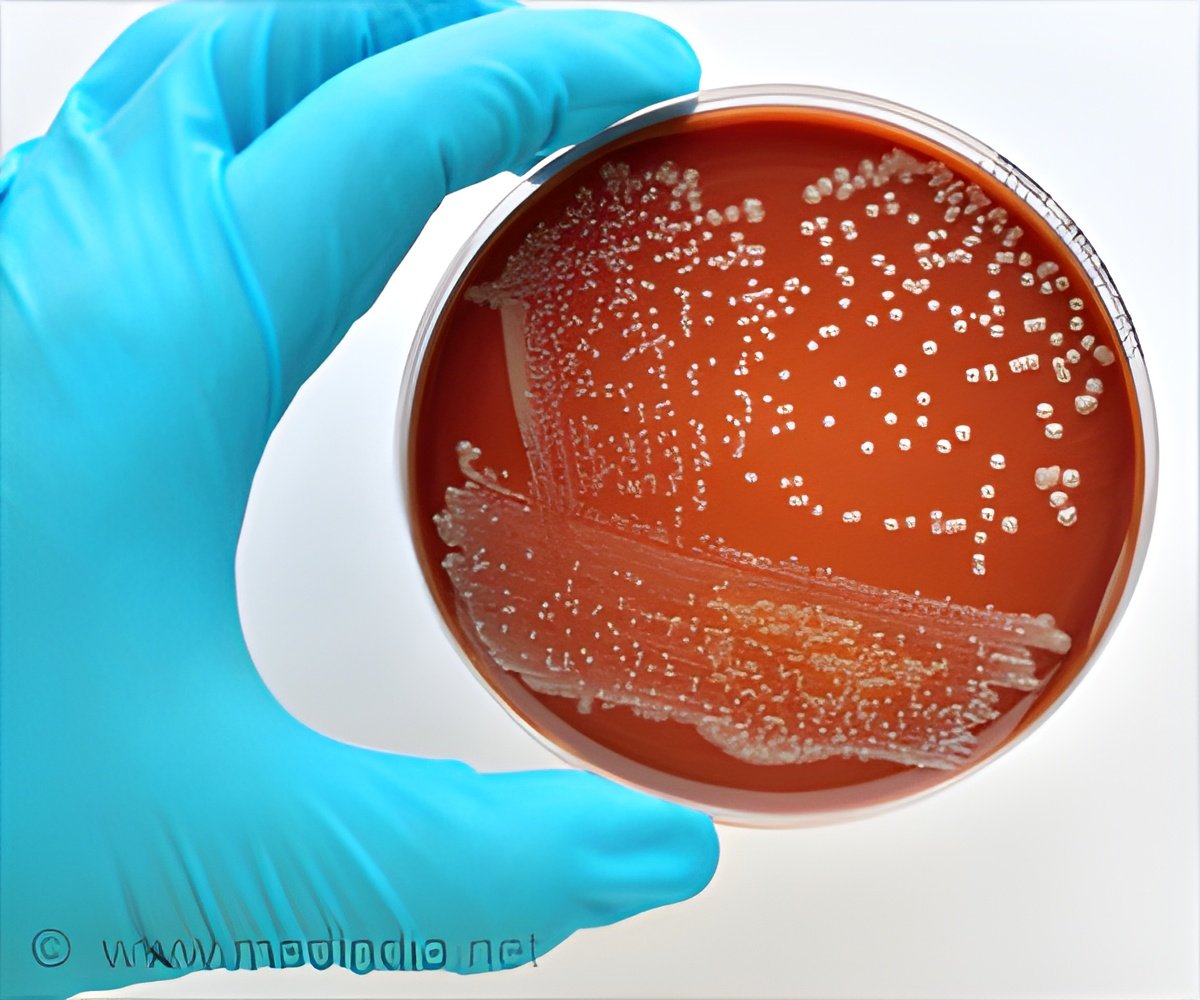

Whether immune training occurs depends on how the DNA of the cell is wrapped. In human cells, for instance, more than 6 feet of DNA must fit into the cell's nucleus, which is so small that it is not visible to the naked eye. To achieve this feat, the DNA is tightly wrapped into chromosomes.

Only selected regions of the DNA are exposed and accessible, and only the genes in those accessible regions are able to respond and fight infection, said senior author Alexander Hoffmann, Professor of Microbiology at UCLA.

However, by introducing a stimulus to a macrophage -- for example, a substance derived from a microbe or pathogen, as in the case of a vaccine -- previously compacted DNA regions can be unwrapped. This unwrapping exposes new genes that will enable the cell to respond more aggressively, in essence training it to fight the next infection, Hoffmann said.

Advertisement