If you wonder what sweaty palms and abnormal heart rhythms have in common, both can be set off by the nervous system during adrenaline-driven flight or fight stress reaction in danger.

UCLA cardiologists have found that surgery to snip nerves related to the sympathetic nervous system on both the left and right sides of the chest, may be helpful in stopping dangerous incessant ventricular arrhythmias -- called an electrical storm -- when other treatment methods have failed. This same type of surgery has been used for years to alleviate hyperhidrosis.

The UCLA team''s findings are reported in the Dec. 27/Jan. 3 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. This is one of the first studies to assess the impact of performing the surgery on both sides of the heart to control arrhythmias, called a bilateral cardiac sympathetic denervation (BCSD). This builds on previous work at UCLA where this procedure was just done on the left side, but to obtain relief, some patients may need the procedure performed bilaterally.

Many people suffer from ventricular arrhythmias, which is the leading cause of death in the U.S. (400,000 deaths/year). These arrhythmias can usually be controlled by medications, an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) that automatically shocks the heart to help bring it back into normal rhythm or a procedure called catheter ablation, which stops the arrhythmia by providing a targeted burn to the tiny area of the heart causing the irregular heart beat.

"When these treatment options fail, especially for a patient experiencing a life-threatening electrical storm, the situation becomes critical. We are always seeking additional options to help patients," said senior study author Dr. Kalyanam Shivkumar, director, UCLA Cardiac Arrhythmia Center and co-director of the Oppenheimer Family Center for Neurobiology of Stress at UCLA.

The UCLA findings add to a growing field of research into the sympathetic nervous system''s impact on stress and possible role in disease. Shivkumar notes that this may provide a unique opportunity. If snipping the cardiac sympathetic nerve proves to effectively alleviate irregular heart rhythms, perhaps this could be a treatment initiated early, before the disease manifests.

Advertisement

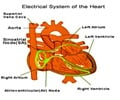

Specifically, surgeons cut the stellate ganglia, part of the sympathetic nervous system that delivers information to the body about stress and initiates the "flight or fight" response. These ganglia contain thousands of nerve cell bodies, and run on either side of the spinal cord in long chains. From these ganglia, nerves then travel to the heart.

Advertisement

For the study, researchers reviewed records from patients at UCLA and a collaborating center in France. The patients presented with electrical storm. The average age was 60 and all were poor candidates for a heart transplant. After other treatments had failed such as medications, catheter ablation and an implantable defibrillator, patients received surgeries to snip the cardiac sympathetic nerves destined for both sides of the heart.

Researchers found that after the surgery, four out of the six study patients completely responded with no more arrhythmias. One patient had a partial response and one had no response at all.

With their heart rhythms stabilized, three of the responding patients received no more shocks from their ICDs, which would previously occur when the devices tried to normalize irregular rhythms. One of these patients had been experiencing 11 shocks a day. The patient who partially responded to treatment had a shock reduction of more than 50 percent.

All five responding patients survived until hospital discharge. Two of the responding patients passed away after discharge due to health issues not related to arrhythmias. No major operative complications occurred in the patients studied. Typical side effects related to this procedure such as alterations in sweating or temperature regulation were not significant. Researchers note that these side effects are usually acceptable to the seriously ill patients who are experiencing an electrical storm, considering that the alternative includes continued arrhythmias, ICD shocks or death.

According to researchers, cutting the cardiac sympathetic nerve may interrupt pro-arrhythmic signaling within the heart tissue or stellate ganglion, thus stopping the irregular heart rhythms.

"We are encouraged by this small study''s results, and plan to further examine the role of this procedure in suppressing arrhythmias in a larger patient population," said Dr. Olujimi Ajijola, a UCLA cardiology fellow and lead author of the study.

"This type of innovative therapy is only possible because of close scientific and clinical collaborations between multiple teams of specialists caring for very sick patients" said co-author Dr. Aman Mahajan, chief of cardiac anesthesia and vice chairman of the Department of Anesthesia at UCLA.

The research by this group in this area was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health.

Source-Newswise