Rogue immune cells are a major contributor to autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and aplastic anemia.

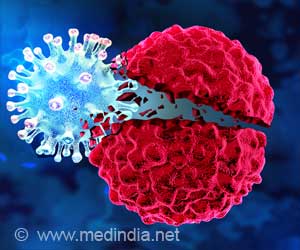

Killer T Cells Involved in Autoimmune Conditions

Gene variations affecting a protein that controls the growth of killer T cells can turn them rogue, the researchers found.‘The new research provides insights into the role that killer T cells play in leukemia and autoimmune diseases.’

“We showed that these rogue killer T cells are driving the autoimmunity. They’re probably one of the cell types most directly contributing to autoimmune disease,” says Dr. Etienne Masle Farquhar, a postdoctoral researcher in the Immunogenomics and Genomic Medicine Labs at Garvan. “Our research also narrows down a few pathways that might be helpful in targeting these cells for future treatments,” he says.

The findings are published in the journal, Immunity.

Cancers can grow when tumor cells are not identified or destroyed by the immune system. Autoimmune diseases occur when the immune system attacks the body’s own cells, mistaking them for harmful or foreign cells.

“We knew that people with various autoimmune diseases acquire these rogue killer T cells over time, but also that inflammation can cause immune cells to proliferate and develop mutations. We set out to discover whether the rogue T cells were causing these autoimmune conditions, or were simply associated with them,” says Dr. Masle Farquhar.

Advertisement

They then used a technique called CRISPR/Cas9, a genome editing tool, in mouse models, to find out what happens when the protein STAT3 is genetically altered.

Advertisement

The team found that if these proteins are altered, they can cause rogue killer T cells to grow unchecked, resulting in enlarged cells that bypass immune checkpoints to attack the body’s own cells.

In addition, even just 1-2% of a person’s T cells going rogue could cause autoimmune disease.

“It’s never been clear what the connection between leukemia and autoimmune disease is – whether the altered STAT3 protein is driving disease, or whether leukemic cells are dividing and acquiring this mutation just as a by-product. It’s a real chicken-and-egg question, which Dr. Masle Farquhar's work has been able to solve,” says Professor Chris Goodnow, Head of the Immunogenomics Lab and Chair of the Bill and Patricia Ritchie Foundation at Garvan.

“This gives some really good cracks in the coalface of where we might do better in terms of stopping these diseases, which are sometimes life threatening,” he says.

Future applications could include better targeting of medication, like already TGA-approved JAK inhibitors, based on the presence of these mutations. “We can now go and look for T cells with STAT3 variations. That’s a big step forward in defining who’s the bad guy,” says Professor Goodnow.

The study also identified two specific receptor systems – ways for cells to talk to one another – that are linked to stress.

“Part of what’s driving these rogue cells to expand as killer T cells is the stress-sensing pathways. There is a lot of correlation between stress, damage, and aging. Now we have tangible evidence of how that’s connected to autoimmunity,” says Professor Goodnow.

The team’s research may help develop screening technologies that clinicians could use to sequence the complete genome of every cell in a blood sample, to identify which cells might turn rogue and cause disease.

Source-Eurekalert