Lymphocytes that correctly detect cancer signals use proteins called T-cell receptors to lock on to these cancer signals and prevent tumor growth.

‘The method promises to illuminate how immune cells lock onto targets, the cellular recognition at the heart of autoimmune disorders and infections.’

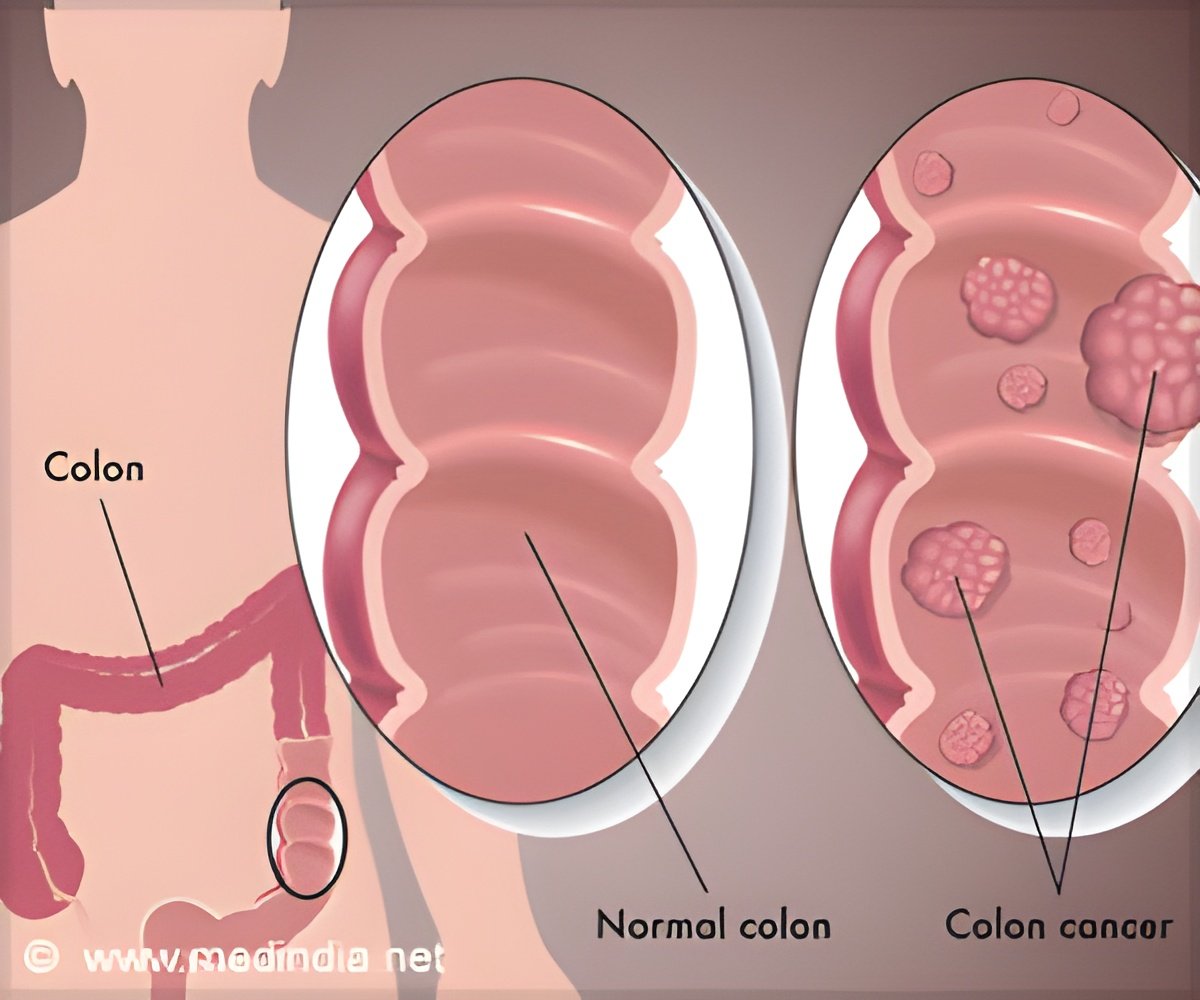

One type of immune cell called a b>tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte, can invade tumors and help destroy cancer cells. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes have captured the attention of cancer researchers eager to supercharge these cells' tumor-killing abilities. This destruction depends on lymphocytes correctly detecting cancer signals - bits of protein called antigens that cancer cells display on their surface. Lymphocytes use proteins called T-cell receptors to lock on to these cancer signals, many of which are unknown.

Along with graduate student Marvin Gee, Garcia enlisted the collaboration of Mark Davis, an HHMI investigator at Stanford University. Davis's laboratory has developed ways to read the DNA sequences of single lymphocytes - information that helped research team hunt for immune cells' targets. First, Davis and post-doctoral fellow Arnold Han isolated and characterized T-cell receptors from two patients with colorectal cancer.

Next, they used those precise T-cell receptors as bait, a labor-intensive process that involves searching through hundreds of millions of signals that cancer cells might display. These signals, short strings of amino acids, represent molecular needles in an enormous haystack.

But the method worked. And the researchers discovered something surprising: Out of a huge number of possibilities, the T-cell receptors from both patients recognized the same tumor antigen. The results support the approach of developing broadly effective cancer treatments based on the immune system. "We have to find antigens that are shared across multiple different patients so that one treatment can serve many different people," Garcia says.

Advertisement

The new results have implications that reach far beyond cancer, too. The method could illuminate the cellular details of autoimmune disorders, infectious diseases or any other process that involves T-cell receptors, Garcia says.

Advertisement

"This is a great example of how starting with the most reductionist approach can lead you to very powerful insights with clinical relevance," he says. "If you invest in the most basic discovery science, and you go deep enough on an important problem, here's what can come out the other end."

Source-Eurekalert