The tattooists bent over Kingi Taurua for 15 hours, using chisels and a stick as a hammer to gouge bold Maori designs into his bloodied face, buttocks and legs.

"They asked me if I wanted a break and I said no, because it was so painful, I thought if I stopped for a minute I won't be able to go back and finish it."

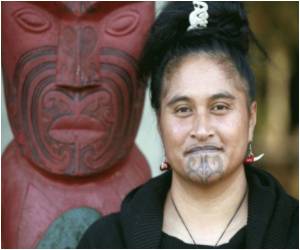

Taurua was following a long line of ancestors in receiving the tattoos, or moko as they are known to New Zealand's indigenous Maori.

The art gradually died in the 19th and early 20th centuries as Maori culture was swamped and suppressed by a wave of European settlers.

But in the last 20 years, Maori culture and tattooing -- ta moko -- have experienced a strong revival and the distinctive dark swirls and designs once again can be seen on a growing number of Maori and on non-Maori as well.

All but a few now opt to have their moko done with modern tattoo machines rather than the painful and bloody traditional chisels or uhi and a range of colours are sometimes used as well as the traditional black.

Advertisements

The word tattoo comes from the Tahitian word tatau and the Maori brought the art form with them when they migrated to New Zealand from eastern Polynesia around 700 to 800 years ago, eventually establishing a distinctive local style.

Advertisements

Facial moko on Maori men recognised high birth and rank, as well as achievements on the battlefield. Men and women of all ranks often had moko on their bodies and women had small tattoos carved on their chins, sometimes with blackened lips.

As Maori culture and society started to weaken with the growing flood of colonists, the tattooing of men's faces ended in the mid-19th century, although the female or kauae moko continued to be done on some women into the 1920s.

A strong revival of Maori language and culture since the 1980s has also seen a resurgence of ta moko, reflecting a renewed pride in Maori identity.

Another influence was the 1994 New Zealand film "Once Were Warriors", a story of domestic violence in a Maori family set against the backdrop of a working class Auckland suburb beset by gang violence.

Auckland-based moko artist Inia Taylor worked on the film before he took up tattooing, and he contributed to the design of the moko-type tattoos which adorned gang members and made a big impact on audiences.

"I didn't know anyone who was involved in moko prior to that film," Taylor told AFP.

"Afterwards, there was a lot of interest, people wanted to get tattooed. There was this massive hunger for it."

Taurua said he was apprehensive about agreeing to a request by his fellow Ngapuhi tribe elders to get a moko in 2000 as a mark of respect for his position as an important elder.

"I was worried that people might see me as a member of a gang rather than a chief of a tribe," he said.

"Afterwards, I didn't know whether to look up or look down when I passed people because I didn't want to see the reaction on their faces, but now after all these years I am getting used to the fact."

Most of the negative reactions come from European New Zealanders, many of whom still associate facial tattoos with gangs, he said.

Ta moko is a sensitive issue in more ways than the physical pain involved, with some Maori, including Taurua, arguing it should continue to be done only for traditional reasons.

"I believe once a moko goes on, it tells a story and it talks about the person wearing it, their genealogy, their ancestors -- it's a story," he said.

"My question is, if you put a moko on somebody from overseas what story is on that moko?".

But ta moko artist Rangi Kipa, from Whakatane on the east coast of the North Island, said the culture Maori live in has changed and ta moko has to reflect that.

"I don't have a problem with the commercial side, as long as we (Maori) are doing it. I do have an issue with other people overseas doing it," Kipa told AFP.

"I have probably 20 clients a year who fly over from the UK or Europe. They just come because they have seen my work on the web and they want to get something.

"A lot of times they are looking to an opportunity to make a statement to themselves and mark themselves with something with meaning -- not like if you just walk into a tattoo store."

Taylor says there is no reason ta moko should be exclusive to Maori as culture becomes more global.

"I'm quite happy for moko to be popular culture because I think that's where it needs to be."

"It's like if people had told (reggae musician) Bob Marley not to play outside Trenchtown, Jamaica."

But he recognises the special significance ta moko has for some Maori.

"The first woman I tattooed by hand (using traditional tools) was an 80-year-old who wanted to be as 'old school' as possible," Taylor said.

"The whole thing was in memory of her grandmother who wore a moko and she wanted to get as close to that experience as possible."

Source-AFP