Bubonic plague, an ancient terror, could provide researchers with new insights on how the body responds to infections, paving way to tackle dangerous new pathogens such as the Ebola virus.

The insight provides a new avenue to develop therapies that block this host immune function rather than target the pathogens themselves – a tactic that often leads to antibiotic resistance.

"The recent Ebola outbreak has shown how highly virulent pathogens can spread substantially and unexpectedly under the right conditions," said lead author Ashley L. St. John, Ph.D., assistant professor, Program in Emerging Infectious Diseases at Duke-NUS Singapore. "This emphasizes that we need to understand the mechanisms that pathogens use to spread so that we can be prepared with new strategies to treat infection."

While bubonic plague would seem a blight of the past, there have been recent outbreaks in India, Madagascar and the Congo. And it's mode of infection now appears similar to that used by other well-adapted human pathogens, such as the HIV virus.

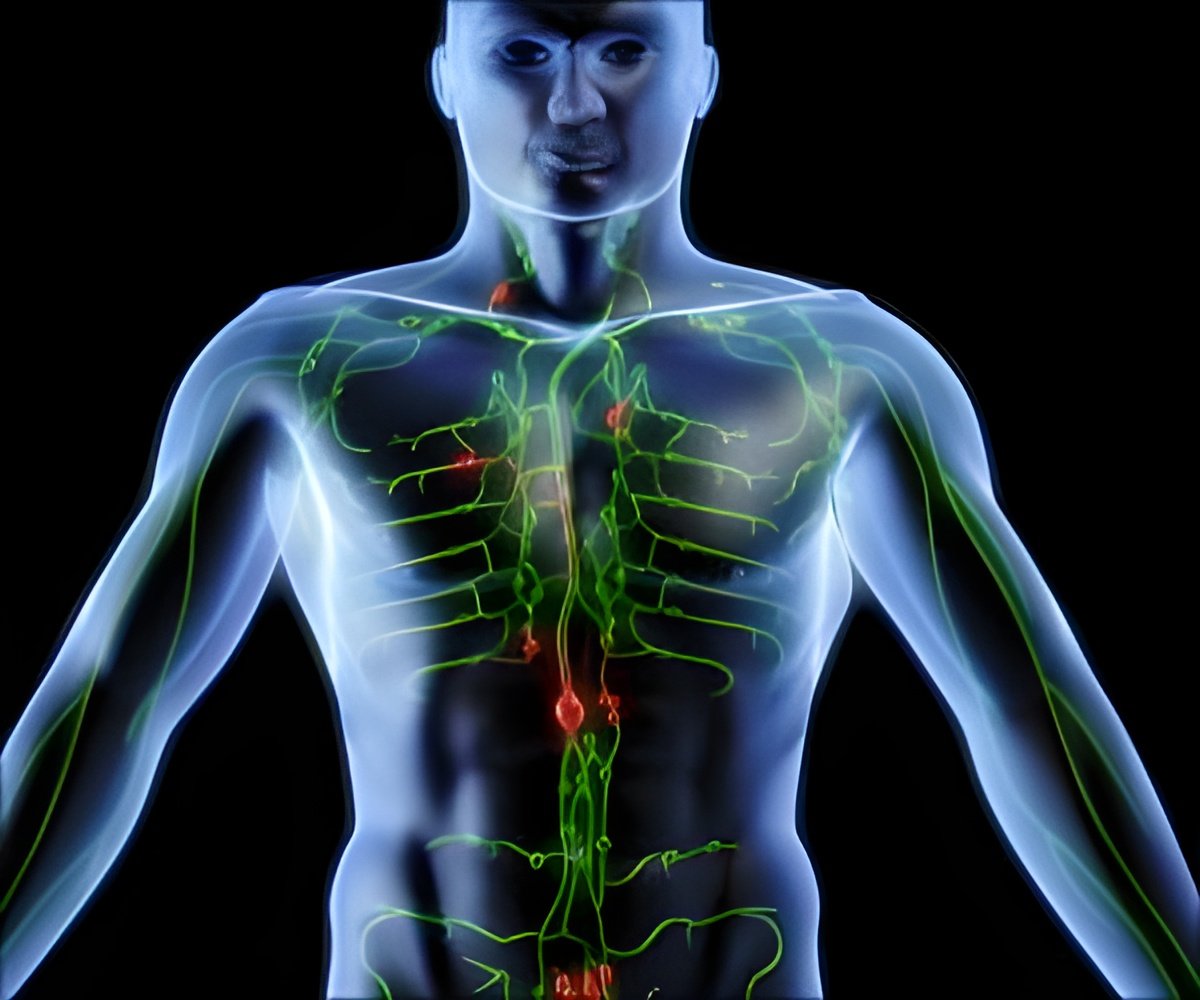

In their study, the Duke and Duke-NUS researchers set out to determine whether the large swellings that are the signature feature of bubonic plague – the swollen lymph nodes, or buboes at the neck, underarms and groins of infected patients – result from the pathogen or as an immune response.

It turns out to be both.

Advertisement

The bacteria are then able to travel from lymph node to lymph node within the dendritic cells and monocytes, eventually infiltrating the blood and lungs. From there, the infection can spread through body fluids directly to other people, or via biting insects such as fleas.

Advertisement

"This work demonstrates that it may be possible to target the trafficking of host immune cells and not the pathogens themselves to effectively treat infection and reduce mortality," St. John said. "In view of the growing emergency of multi-resistant bacteria, this strategy could become very attractive."

Source-Eurekalert