Initially it was feared that diseases such as cholera would take the heaviest toll on survivors of the Indian Ocean tsunami. But overcrowding at

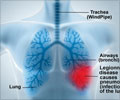

Initially it was feared that diseases such as cholera would take the heaviest toll on survivors of the Indian Ocean tsunami. But overcrowding at refugee camps has intensified the spread of pneumonia, and health officials fear that respiratory diseases may claim many lives in the already devastated region.

In the days following the tsunami on 26 December last year, groups such as the World Health Organization issued statements alerting people to the possibility that diarrhoea-type diseases, particularly cholera, would spread rapidly. Cholera outbreaks typically begin to appear one to two weeks after a catastrophe, as unclean drinking water and damaged sewage systems accumulate the bacteria that cause the disease.But although doctors had seen several hundred cases of diarrhoea in the affected countries, no one had reported a cholera outbreak as of Friday 7 January. The number of people suffering from diarrhoea does not exceed the typical level of the illness usually found in the region, experts say.

Medical teams on the lookout for cholera have instead seen respiratory diseases on the rise. "The biggest killer is pneumonia," says Hakan Sandbladh, health officer for emergency relief at the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Rainy weather and lack of shelter in hard-hit countries such as Sri Lanka have left people more vulnerable to this type of illness, he says.

Fighting chance With proper treatments and sanitation efforts, there is a chance that outbreaks of cholera might not materialize. "We don't want to make these illnesses sound inevitable," says Martyn Broughton, a spokesman for the London branch of the medical charity Médecins Sans Frontières.

Courtesy Nature