After a successful clinic trial in animal models, the University of Alabama at Birmingham is to test how a common blood pressure drug can cure diabetes in humans.

The trial, known as “the repurposing of verapamil as a beta cell survival therapy in type 1 diabetes,” is scheduled to begin early next year and has come to fruition after more than a decade of research efforts in UAB’s Comprehensive Diabetes Center.

The trial will test an approach different from any current diabetes treatment by focusing on promoting specialized cells in the pancreas called beta cells, which produce insulin the body needs to control blood sugar. UAB scientists have proved through years of research that high blood sugar causes the body to overproduce a protein called TXNIP, which is increased within the beta cells in response to diabetes, but had never previously been known to be important in beta cell biology. Too much TXNIP in the pancreatic beta cells leads to their deaths and thwarts the body’s efforts to produce insulin, thereby contributing to the progression of diabetes.

But UAB scientists have also uncovered that the drug verapamil, which is widely used to treat high blood pressure, irregular heartbeat and migraine headaches, can lower TXNIP levels in these beta cells — to the point that, when mouse models with established diabetes and blood sugars above 300 milligrams per deciliter were treated with verapamil, the disease was eradicated.

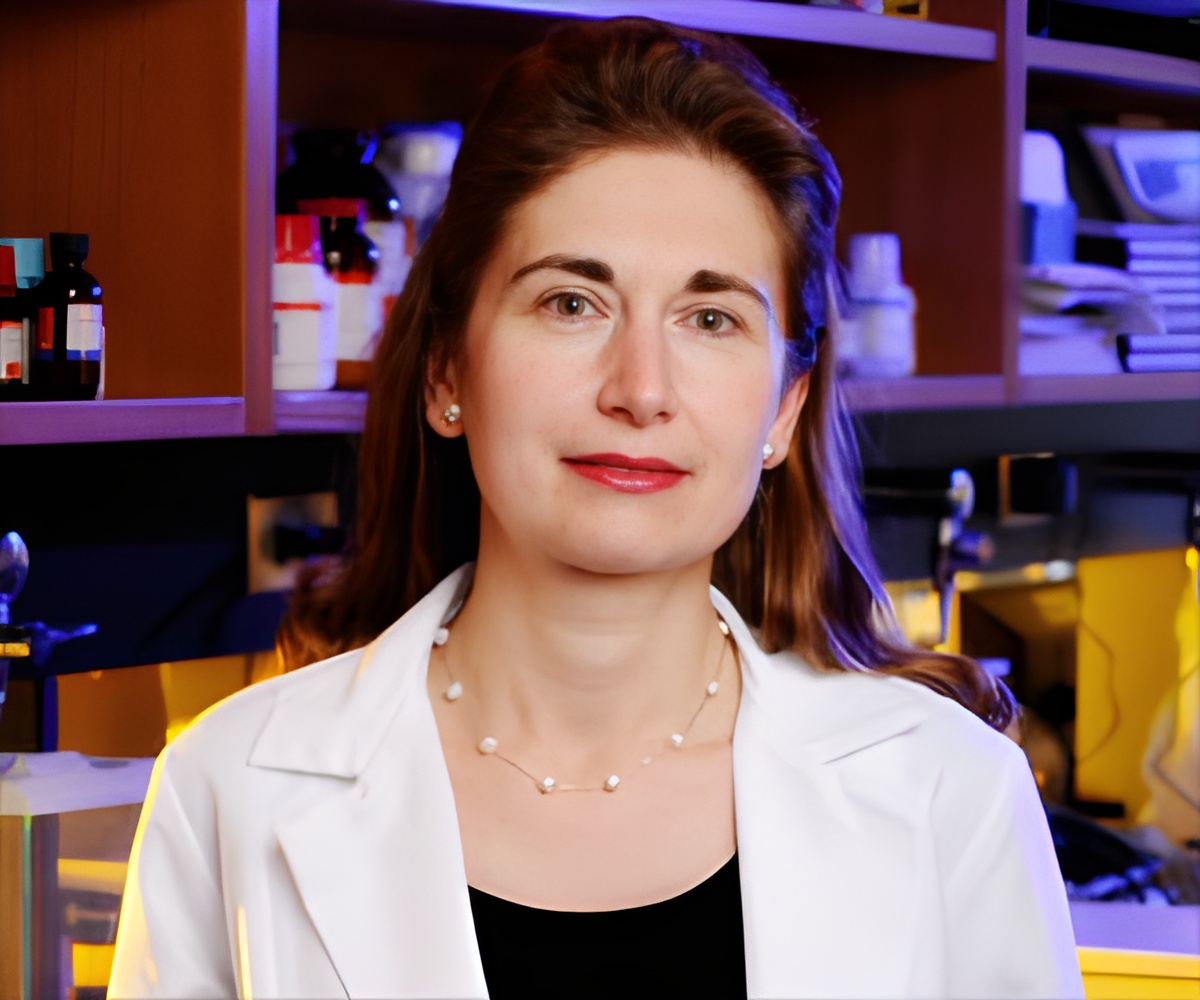

“We have previously shown that verapamil can prevent diabetes and even reverse the disease in mouse models and reduce TXNIP in human islet beta cells, suggesting that it may have beneficial effects in humans as well,” said Anath Shalev, M.D., director of UAB’s Comprehensive Diabetes Center and principal investigator of the verapamil clinical trial. “That is a proof-of-concept that, by lowering TXNIP, even in the context of the worst diabetes, we have beneficial effects. And all of this addresses the main underlying cause of the disease — beta cell loss. Our current approach attempts to target this loss by promoting the patient’s own beta cell mass and insulin production. There is currently no treatment available that targets diabetes in this way.”

The trial will enroll 52 people between the ages of 19 and 45 within three months of receiving a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. Patients enrolled will be randomized to receive verapamil or a placebo for one year while continuing with their insulin pump therapy. In addition, they will receive a continuous glucose monitoring system that will enable them to measure their blood sugar 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Advertisement

“Currently, we can prescribe external insulin and other medications to lower blood sugar; but we have no way to stop the destruction of beta cells, and the disease continues to get worse,” Ovalle said. “If verapamil works in humans, it would be a truly revolutionary development in a disease affecting more people each year to the tune of billions of dollars annually.”

Advertisement

Diabetes, which is the nation’s seventh-leading cause of death, raises risks for heart attacks, blindness, kidney disease and limb amputation. Recent federal government statistics show that 12.3 percent of Americans 20 and older have diabetes, either diagnosed or undiagnosed. Another 37 percent have pre-diabetes, a condition marked by higher-than-normal blood sugar. That is up from 27 percent a decade ago.

While a new report in the Journal of the American Medical Association showed rates at which new cases are accumulating have slowed in recent years, the numbers remain high and are still increasing overall, with 8.3 percent of adults diagnosed with the disease as of 2012. And no slowing of the disease has been seen in new cases among blacks and Hispanics or in overall rates among people with high school educations or less.

Plus, the annual cost to treat the disease is exorbitant — and rising. The American Diabetes Association reports that the disease cost the nation $245 billion in 2013.

Researchers have known for some time that beta cells are critical in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The cells are gradually lost in both types of the disease due to programmed cell death, but the exact triggers for the deaths were previously unknown. Somewhat surprisingly, it was also noted that, after years — decades, even — of living with type 1 diabetes, where beta cells were thought to be completely destroyed early on by the autoimmune process, patients still had a measurable amount of beta cell function; it just was not enough to maintain a normal blood sugar.

Shalev says replacing this beta cell mass by transplantation has proved more difficult and problematic than initially thought, but creating an environment that would enable beta cells to survive and possibly regenerate or become functional again does provide an attractive alternative by increasing the body’s own beta cell mass. UAB lab studies have shown verapamil to be extremely effective in this area, which has helped to make this clinical trial — funded by the JDRF, the largest charitable supporter of type 1 diabetes research — a possibility now.

JDRF is funding this study as part of its beta cell restoration research program whose goal is to restore a person’s ability to produce their own insulin — in essence, a biological cure for type 1 diabetes.

"A first step towards that goal may be the ability to improve the survival and functioning of a person’s beta cells shortly after diagnosis," said JDRF director of Discovery Research, Andrew Rakeman, Ph.D. "This study represents the result of years of investment in basic research at JDRF. We are now at the stage of translating basic laboratory research into potential significant new therapies for type 1 diabetes and we’re excited to support Dr. Shalev’s team to test this concept in a study of people with type 1 diabetes. Finding a therapy to improve beta cell survival and functioning would put JDRF’s efforts to find a cure on a new trajectory."

Ovalle will manage all patients with the use of insulin pumps and continuous glucose sensors and co-manage patients who are already seeing another endocrinologist remotely. UAB’s clinic team will analyze patients’ blood sugar control and their ability to produce insulin. They will also use a more complex test known as c-peptide response as a way to measure beta cell insulin production and functional beta cell mass.

One of the truly unique and different aspects of this clinical trial is that, unlike most type 1 diabetes trials, the verapamil trial does not include the use of any immunosuppressive or immune modulatory medications, which often have very severe side effects.

“This trial is based on a well-known blood pressure medication that has been used for more than 30 years and is unlikely to have any severe side effects,” Shalev said. “This study is also backed by a lot of strong mechanistic data in different mouse models and human islets, and we already know the mechanisms by which verapamil acts. Finally, unlike any currently available diabetes treatment, the trial targets the patient’s own natural beta cell mass and insulin production.”

A first step

Shalev says the trial is a first step in the direction of such a novel diabetes treatment approach. “While in a best-case scenario, the patients would have an increase in beta cells to the point that they produce enough insulin and no longer require any insulin injections — thereby representing a total cure — this is extremely unlikely to happen in the current trial, especially given its short duration of only one year,” Shalev said.

Shalev expects verapamil to have a much more subtle yet extremely important effect.

“We know from previous large clinical studies that even a small amount of the patient’s own remaining beta cell mass has major beneficial outcomes and reduces complications,” Shalev said. “That’s probably because even a little bit of our body’s own beta cells can respond much more adequately to very fine fluctuations in our blood sugar — much more than we can ever do with injections or even sophisticated insulin pumps.”

Because verapamil’s mode of action is different from current drugs or interventions, this opens up an entirely new field for diabetes drug discovery — one that UAB’s Comprehensive Diabetes Center is already engaged in with the Alabama Drug Discovery Alliance, a partnership between UAB’s School of Medicine and Southern Research Institute. The group is actively looking for small therapeutic molecules that inhibit TXNIP to protect the beta cells and treat diabetes.

“We want to find new drugs — different from any current diabetes treatments — that can help halt the growing, worldwide epidemic of diabetes and improve the lives of those affected by this disease,” Shalev said. “Finally, we have reason to believe that we are on the right track.”

Shalev says none of the research leading up to this point - nor the clinical trial itself - would have been possible without the existence of the UAB Comprehensive Diabetes Center and the continued support of the community. Support this and other diabetes research at UAB by visiting the Comprehensive Diabetes Center.