As Tokyo pledged $2 billion to help poorer nations combat pollution, a UN conference adopted a treaty on mercury control near the site of Japan's worst industrial poisoning.

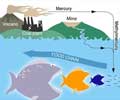

The Minamata Convention on Mercury is named after the Japanese city where tens of thousands of people were sickened -- around 2,000 of whom have since died -- by eating fish and shellfish taken from waters polluted by discharge from a local factory.

Minamata is a byword in Japan for sluggish official responses and the development-at-all costs that characterised the decades of booming growth after World War II.

A doctor who was seeing patients whose immune systems were hit or who had developed brains or nervous system problems first flagged the issue in the mid 1950s and industrial pollution was suggested as a possible cause shortly thereafter.

But it was not until 1968 that the factory stopped pumping out its mercury-laden waste.

In a video message sent to the opening ceremony Wednesday, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe pledged $2 billion to help developing nations address environmental pollution between 2014 and 2016.

Advertisement

But the comments provoked ire in Minamata, where many are still suffering the effects of decades of toxic dumping.

Advertisement

The treaty sets a phase-out date of 2020 for a long list of products -- including mercury thermometers -- and gives governments 15 years to end all mercury mining.

But environmental groups say it stops short of addressing the use of mercury in artisanal and small-scale gold mining, which directly threatens the health of miners including child labourers in developing countries.

They also warn of health risks from eating

The treaty will take effect once ratified by 50 countries -- something organiser the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) expects will take three to four years.

"It's necessary that many developing nations ratify the treaty so that it takes effect in an early date," Japanese environment minister Nobuteru Ishihara said at the opening ceremony.

A UNEP report issued last year said the spiralling use of chemicals, especially in developing countries, is damaging people's health and the environment.

Many developing countries lack safeguards for handling chemicals safely or disposing of them properly, according to the report, entitled "Global Chemicals Outlook".

"Poor management of volatile organic compounds is responsible for global economic losses estimated at $236.3 billion (188 billion euros)," the UNEP said.

"Exposure to mercury results in health and environmental damage estimated at $22 billion," it said.

Source-AFP