Results of a small clinical trial show that a vaccine used to treat women with high-grade precancerous cervical lesions triggers an immune cell response within the damaged tissue itself.

"It's difficult to measure immune cell responses to therapeutic vaccines, but we believe that clinical studies could tell us more about the value and function of the vaccines if we check for the response in the lesions, where the immune system is fighting precancerous cells," says Connie Trimble, M.D., associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics, oncology and pathology at Johns Hopkins' Kimmel Cancer Center.

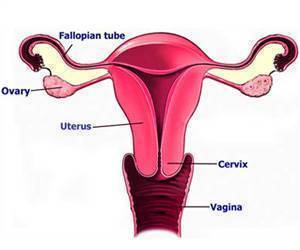

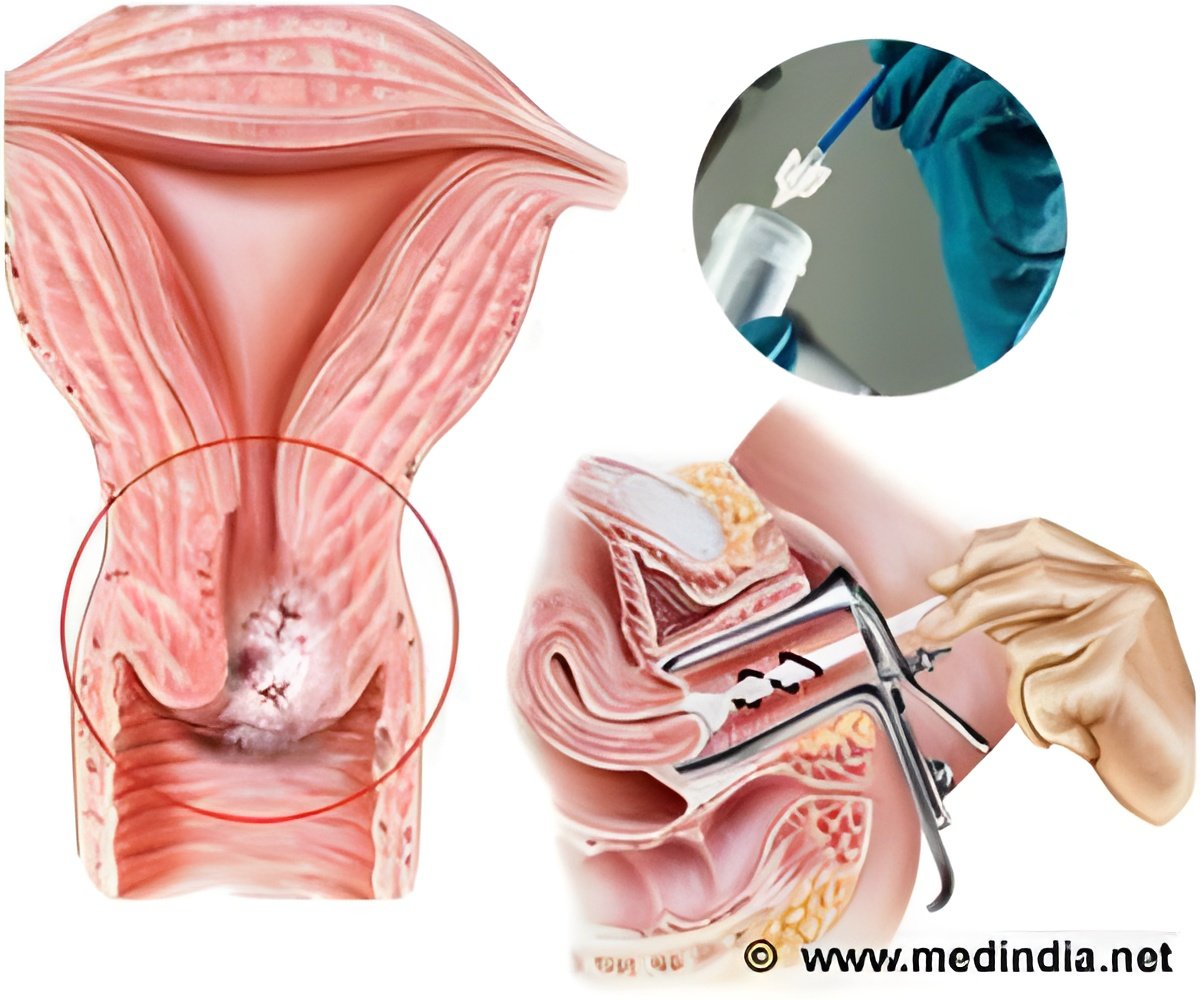

Results of the first 12 women enrolled at Johns Hopkins on a clinical trial led by Trimble are reported online in the Jan. 29 issue of Science Translational Medicine. Each of the women was diagnosed with high-grade precancerous cervical lesions linked to a strain of the human papillomavirus (HPV16) most commonly associated with cervical cancer. In a bid to treat the lesions and prevent cervical cancer, they received three vaccine injections in the upper arm over an eight-week period.

Two types of vaccines were used for the study: one constructed with genetically engineered DNA molecules that teach immune system cells to recognize premalignant cells expressing HPV16 E7 proteins, and one that is a non-infectious, engineered virus that targets and kills precancerous cells marked by HPV16 and HPV18 E6 and E7 proteins.

Seven weeks after the third vaccination, the investigators surgically removed cervical lesions from all of the women. Blood samples and cervical tissue were collected from each patient at the beginning and end of the trial, letting scientists compare immune cell responses before and after vaccination.

In three of six patients treated with the highest dose of the vaccine, and one patient in each of the two groups receiving lower doses of the vaccine, the cervical lesions disappeared. The first patient was treated in 2008, and the 12th in 2012. None of the 12 patients has, so far, developed more lesions.

Advertisement

"We found striking immune system changes within cervical lesions, which were not as evident in the patients' peripheral blood samples," says Trimble.

Advertisement

The Johns Hopkins team says it plans to enroll some 20 more patients, testing a combination of the vaccines and a topical cream to enhance the immune response locally.

Trimble explains that the location of cervical lesions gives scientists an advantage in their vaccination approach. "It's important that we can monitor these cervical lesions closely," says Trimble.

She says that the conventional practice of measuring vaccine effectiveness via blood tests probably began with mouse models used for immunotherapy research. "But the way that HPV and the immune system behave in humans may be far different," she says.

HPV causes nearly all cervical, anal, vaginal, and penile cancers and nearly two-thirds of oral cancers. In the cervix, about 20 to 25 percent of high-grade lesions will disappear spontaneously. Because there is no standard way to predict lesions that will disappear, the current standard of care for these lesions is surgical removal. Current preventive vaccines for HPV are not effective on women already exposed to the ubiquitous virus.

Source-Eurekalert