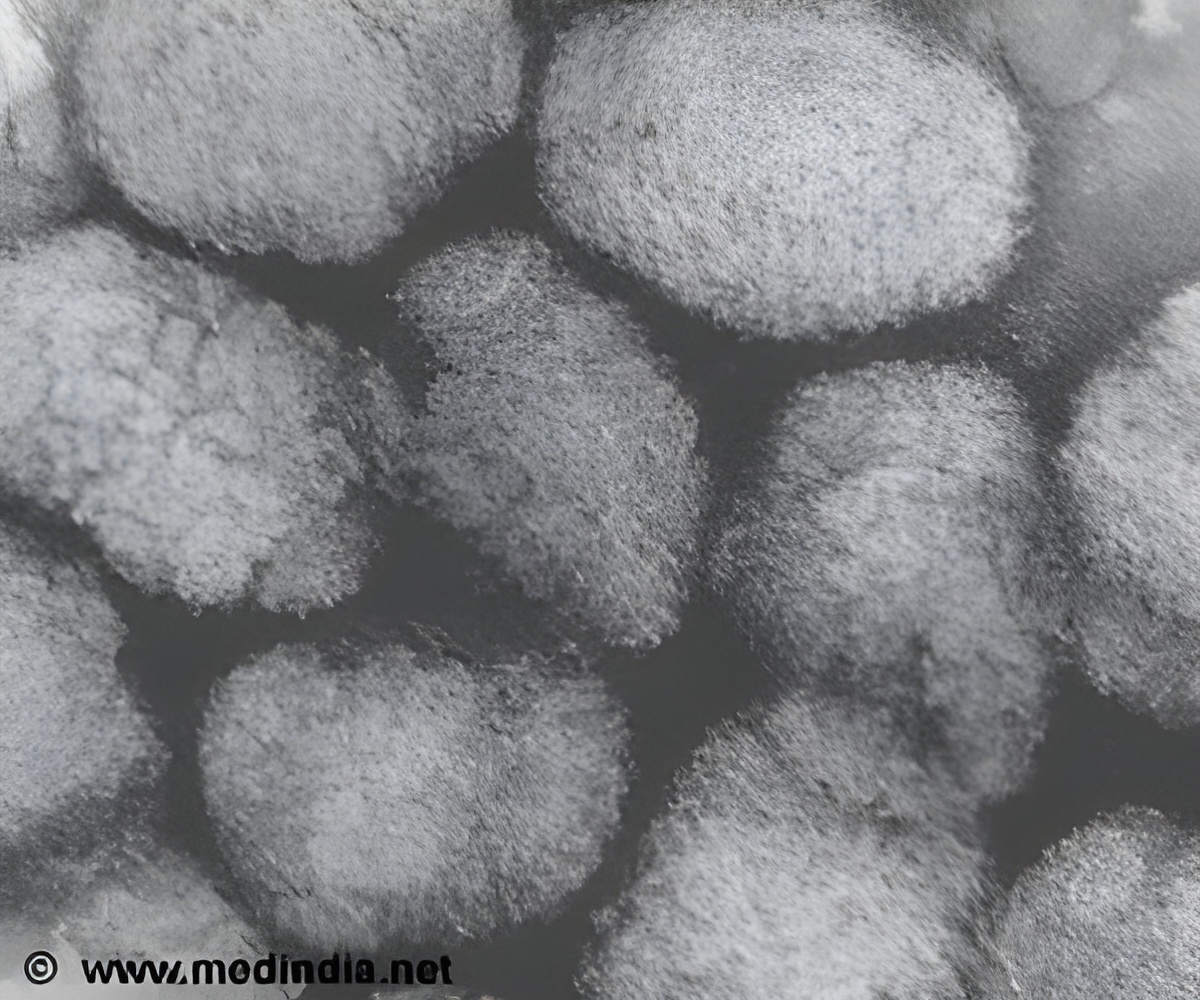

A virtually ignored virus, that most of us carry, is thought to be the top cause of congenital birth defects.

"CMV is recognised as a major pathogen by Clinicians, yet there is little public awareness of the virus." says Professor Gavin Wilkinson from the Cardiff University School of Medicine. "More children have disabilities from this disease than other well-known congenital problems, such as Down's syndrome or fetal alcohol syndrome."

"We have identified a novel trick that this virus uses to hide from immune detection," says La Jolla Institute scientist Chris Benedict, Ph.D., a CMV expert. "By uncovering this mechanism, we've provided an important piece of the CMV puzzle that could enable vaccine counter strategies that flush out and eliminate virus-infected cells." The finding was published online today in the journal Cell, Host & Microbe.

CMV's stealthy nature keeps it under wraps. In common with other member of the herpes family of viruses that cause cold sores, chicken pox and other maladies - once contracted, CMV never goes away. Most people are unaware they have contracted the virus, nor generally do they exhibit any visible symptoms during lifelong carriage. However, research is now revealing how hard that the immune system has to fight to keep CMV at bay.

"In addition to causing terrible birth defects and severe disease in patients with autoimmune disease, CMV induces changes in the immune response of anyone carrying the virus," according to Professor Wilkinson. The constant struggle to control CMV contributes to the immune system 'tiring' over time.

In their study, researchers found that a specific CMV gene (called UL141) blocks the ability of two key immune pathways to kill CMV-infected cells. As their names imply, these two pathways – known as TRAIL "death receptor" 1 and 2 – normally act to kill infected cells.

Advertisement

The TRAIL molecule and its receptors were discovered about 15 years ago and are members of the tumor necrosis factor family of molecules, which have proven extremely important in medical research efforts to control or prevent many diseases. The research team was the first to identify a herpes virus function (UL141) interacting with the TRAIL Death receptors, and it is only the second known protein known to do so (TRAIL is the other).

Advertisement