- Intestinal atresia and Stenosis: Cincinnati Children’s - (https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/health/i/obstructions)

- Small Bowel atresia (Intestinal atresia): Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia - (http://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/small-bowel-atresia)

- Intestinal atresia and Stenosis: Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh - (http://www.chp.edu/our-services/transplant/intestine/education/intestine-disease-states/intestinal-atresia)

- Intestinal atresia: Sanford Health - (http://www.sanfordhealth.org/medical-services/fetal-care-center/learn/intestinal-atresia)

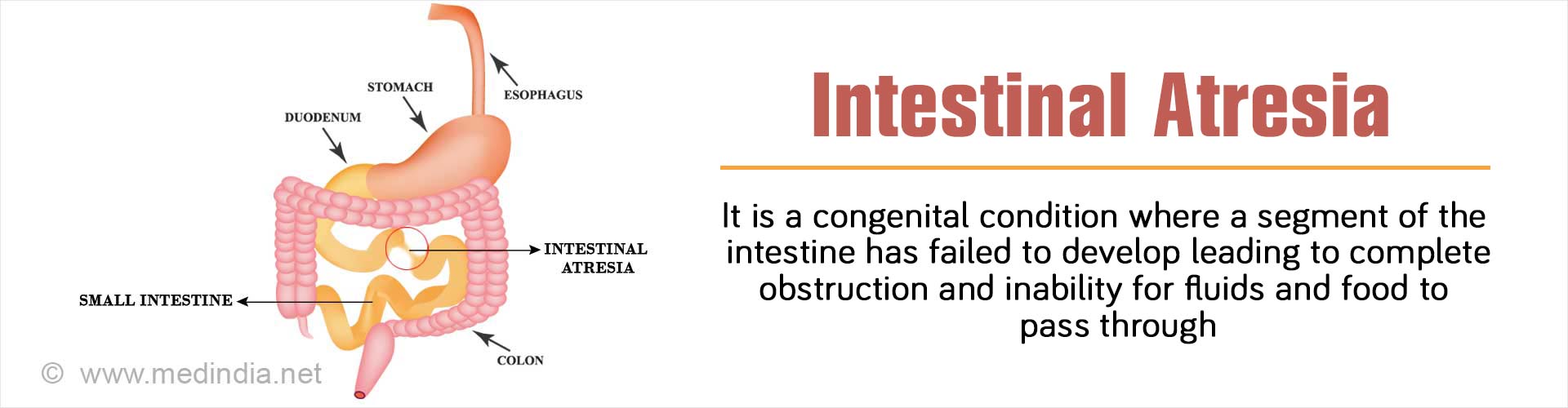

What is Intestinal Atresia?

The term "atresia" is derived from the Greek a- (no or without) and tresis (hole or orifice) and refers to an inherited condition where obstruction and complete occlusion of the intestinal lumen occurs, which accounts for approximately 95% of all obstructions. Thus, atresia is the complete blockage or obstruction of any part of the intestine along the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. There may also be absence of an entire portion of the intestine due to complete obliteration and separation into two separate parts. This contrasts with intestinal stenosis, which is the partial blockage of the intestine.

Although intestinal atresia can occur anywhere along the GI tract, it is generally confined to the small intestine. The frequency of occurrence, symptoms, and methods of diagnosis of intestinal atresia differ according to the site affected.

On an average intestinal atresia occurs in 1 in every 1,500 live births and affects both males and females equally.

What are the Different Types of Intestinal Atresia?

Intestinal atresia may be of several types, depending upon the portion of the intestine affected. These include the following:

Pyloric Atresia:

This type of atresia occurs at the pylorus, the junction between the stomach and the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine. Pyloric atresia occurs in approximately 1 in a million live births. Pyloric atresia is inherited and is generally a rare condition. Affected children tend to vomit out the stomach contents. The stomach becomes filled with gas, resulting in distension of the upper abdomen. X-ray of the abdomen is used for confirmation of the clinical findings.

Duodenal Atresia:

The duodenum is the first part of the small intestine into which the stomach contents are emptied. Duodenal atresia occurs in approximately 1 in 6,000 to 1 in 10,000 live births and is one of the most common congenital small bowel obstructions diagnosed prenatally. Approximately 50% of the infants with duodenal atresia are premature at birth. About 66% have abnormalities of the heart, genitourinary or intestinal tract. Duodenal atresia is strongly associated with Down syndrome. Almost 40% infants have Down syndrome. Infants with duodenal atresia usually vomit soon after birth, and their abdomen becomes distended. X-ray images show a large distended stomach and duodenum without any gas elsewhere along the GI tract.

Jejunoileal Atresia:

This type of atresia occurs in the jejunum (middle portion) or ileum (lower portion) of the small intestine. The most common type of neonatal intestinal obstruction, jejunoileal atresia occurs in 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 3,000 live births. Immediately before the constriction, the intestine is greatly dilated since it is not able to absorb nutrients and transport the accumulated food further down the GI tract. In approximately 10-15% of infants with jejunoileal atresia, parts of the intestine can become degenerated during fetal development. A large number of infants with jejunoileal atresia have problems with intestinal rotation and fixation. It has been found that cystic fibrosis is associated with jejunoileal atresia and can complicate the management of the condition. Jejunoileal atresia is classified into four types (Type I to Type IV) on the basis of severity. The newborn exhibits specific clinical symptoms depending upon the severity of the disease. These include abdominal distension and frequent vomiting of green bile.

Colonic Atresia:

This is a rare form of atresia that exhibits signs and symptoms similar to jejunoileal atresia with highly enlarged bowel. Colonic atresia is often associated with small bowel atresia, Hirschsprung’s disease or gastroschisis.

What are the Causes of Intestinal Atresia?

Intestinal atresia is an inherited condition due to a genetic defect. An example is familial multiple intestinal atresia. One of the most common causes of intestinal atresia is due to a vascular accident, resulting in inadequate blood supply to the intestine of the developing fetus. This leads to ischemia in the respective segment of the intestine, resulting in loss of functionality.

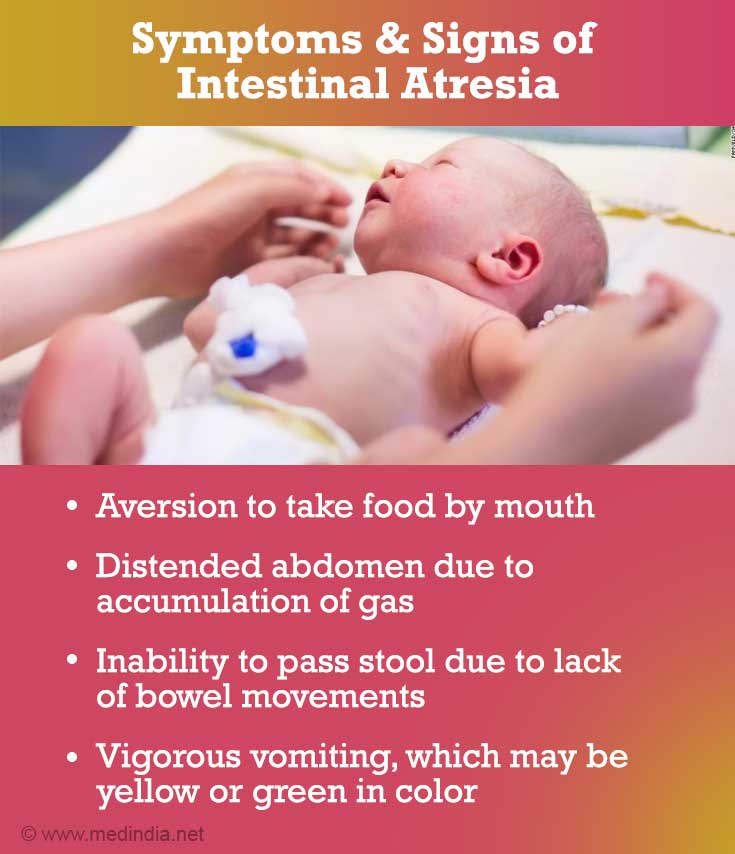

What are the Symptoms and Signs of Intestinal Atresia?

Some of the symptoms and signs of intestinal atresia can be observed even before birth, including polyhydramnios. In this condition, there is more amniotic fluid in the uterus than normal. This occurs due to the inability of the developing fetus to absorb the amniotic fluid through the intestine. A prenatal fetal ultrasound can confirm the diagnosis. After birth, the following symptoms may be observed:

- Aversion to take food by mouth.

- Distended abdomen due to accumulation of gas.

- Inability to pass stool due to lack of bowel movements.

- Vigorous vomiting, which may be yellow or green in color.

How do you Diagnose Intestinal Atresia?

Diagnosis of intestinal atresia can be divided into two phases - prenatal and postnatal diagnosis.

Prenatal Diagnosis

Intestinal atresia is nowadays diagnosed by prenatal ultrasound. A prenatal diagnosis of intestinal atresia is typically made in the third trimester of pregnancy, when the bowel becomes easier to see on ultrasound. Some diagnostic features found prenatally include the following:

- Distended Bowel: A prenatal ultrasound will detect a distended (expanded) bowel before the obstruction.

- Double Bubble: This is a classic sign of duodenal atresia, when there is a dilated bowel and fluid in the stomach and duodenum but not further down.

- Polyhydramnios: This is the presence of excessive amounts of amniotic fluid in the uterus of a pregnant woman, which peaks in the third trimester of pregnancy and is caused by the failure of the intestine to absorb amniotic fluid. Polyhydramnios accompanies 53% cases of duodenal atresia and 25% of cases of jejunoileal atresia.

Due to the high incidence of associated birth defects, a complete prenatal evaluation and amniocentesis are recommended for mothers carrying babies with small bowel atresia to exclude any of the following conditions:

- Cystic Fibrosis

- Down Syndrome

- Congenital Heart Disease

- Bowel Rotational Abnormality

- Annular Pancreas

- Esophageal Atresia

- Anorectal Atresia

- Genitourinary Malformations

Postnatal Diagnosis

Besides prenatal diagnosis, postnatal (after birth) diagnosis can also be carried out. Babies with small bowel atresia tend to vomit frequently, which in itself is an indication that there is something wrong, thereby warranting further investigation. Some specific diagnostic modalities to detect small bowel atresia as well as congenital deformities include the following:

- Abdominal X-Ray: An abdominal X-ray can be used to take images of the internal structures of the baby’s abdomen. This diagnostic investigation can often clinch the diagnosis.

- Upper GI Tract X-Ray: This procedure investigates any abnormalities in the upper GI tract, primarily the pylorus and duodenum. A contrast medium such as barium is administered through the mouth as a barium meal, which makes the internal structures clearer and more distinct on radiographs. X-ray photographs are then taken to evaluate the structures of the upper GI tract.

- Lower GI Tract X-Ray: This procedure investigates the rectum, large intestine and the lower part of the small intestine. A contrast media is administered into the rectum as an enema. This contrast media is radio-opaque and coats the inner lining of the intestine. As a result, X-ray radiographs clearly shows the internal structures of the lower GI tract in minute detail, so that malformations such as strictures (narrowing of the lumen) and obstructions can be easily identified.

- Abdominal Ultrasound: Ultrasonography (USG) is a non-invasive investigative technique that uses sound waves to visualize the functionality of internal organs. These sound waves are emitted from a transducer that is placed on the surface of the body, and the sound waves get deflected by the internal organs and produce a visual image on a monitor. Abdominal ultrasound is used to detect and confirm any abnormalities within the abdomen of babies exhibiting clinical signs of intestinal atresia.

- Echocardiography: Babies born with intestinal atresia can suffer from life-threatening complications such as congenital heart defects. Echocardiography is used to diagnose any congenital abnormalities of the heart.

How do you Treat Intestinal Atresia?

There is no prenatal treatment for babies diagnosed with intestinal atresia. Babies born with intestinal atresia require surgical intervention. The type of surgery involved depends on the nature and location of the blockage. The treatment strategy can be divided into the following stages:

Stabilization:

Prior to surgery, the baby needs to be stabilized.

- A nasogastric tube is inserted through the nose down to the stomach in order to empty the stomach contents and accumulated gas under slight negative pressure. This will prevent the baby from vomiting and aspiration.

- Nutrition will be provided via an intravenous (IV) channel.

- Any investigative procedures such as X-rays and routine blood tests will be carried out during this period, prior to the surgery.

Surgery:

The surgery is done under general anesthesia (GA) so that the baby does not feel any pain or discomfort. The surgery may either be an open surgery or a laparoscopic surgery.

In case of an open type of surgery, a single large incision will be made in the abdomen and the affected portion of the intestine will be excised and the two ends will be sutured so that continuity is maintained. In case of laparoscopic surgery, several small incisions will be made, through which a camera and other instruments will be inserted in order to perform the surgery.

If the intestine requires a relatively longer time to heal, the surgeon may create a stoma (an opening). This is where the intestine is brought to the abdominal skin surface so that the feces can be collected and temporarily stored in a colostomy bag, instead of passing through the anus.

Post-surgical Care:

Post-surgical care is crucial for the baby’s full recovery. The baby is transferred to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) where the vital signs are monitored round-the-clock. Nutrition will continue to be provided through the nasogastric tube until the baby is able to take food by mouth. The duration of the hospital stay may vary between 1 to 3 weeks, depending on how quickly the baby recovers. After discharge from the hospital, a follow-up appointment with the surgeon is required for assessment of the growth parameters and general health and wellbeing of the baby.