- Short Bowel Syndrome - (https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/short-bowel-syndrome/)

- Growth Factors: Possible Roles for Clinical Management of the Short Bowel Syndrome - (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc2891767/?tool=pubmed)

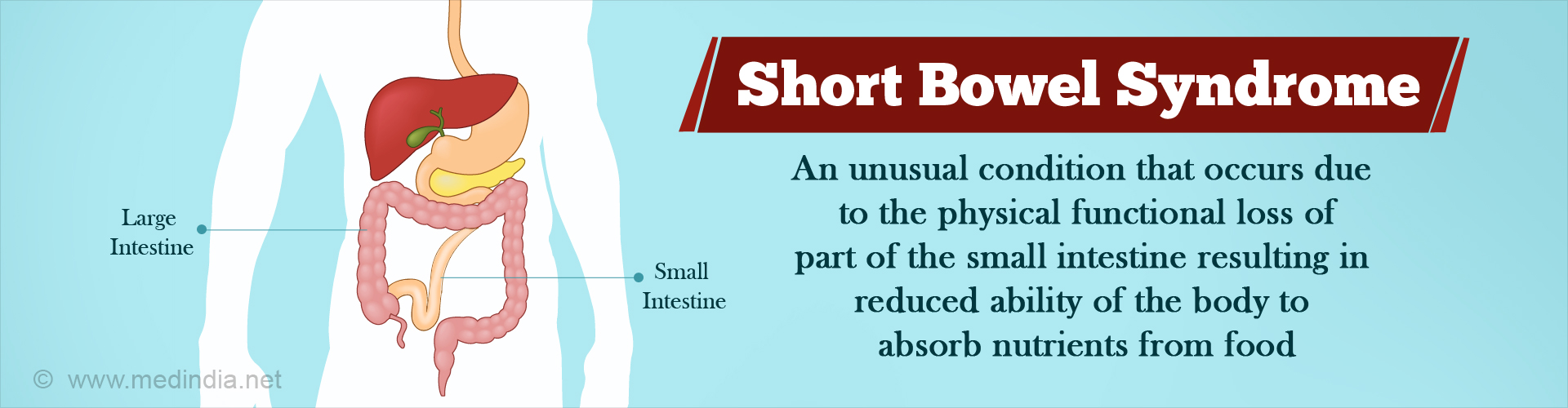

What is Short Bowel Syndrome?

Short bowel syndrome is a rare condition. It is also called short gut syndrome. It is caused due to the absence of the functional part of the small intestine resulting in a malabsorption disorder. It is majorly secondary in nature, resulting from a surgical removal of the functional part of the small intestine.

The human small intestine is on an average 6.1 m (20 feet) long. But when the major portion of the intestine is removed and less than 2m of functional small intestine remains, it is known as short bowel syndrome. This is one of the most common causes of intestinal failure with diarrhea as the commonest presenting symptom. The effect of short bowel syndrome can be devastating in children since they require increased calories to grow.

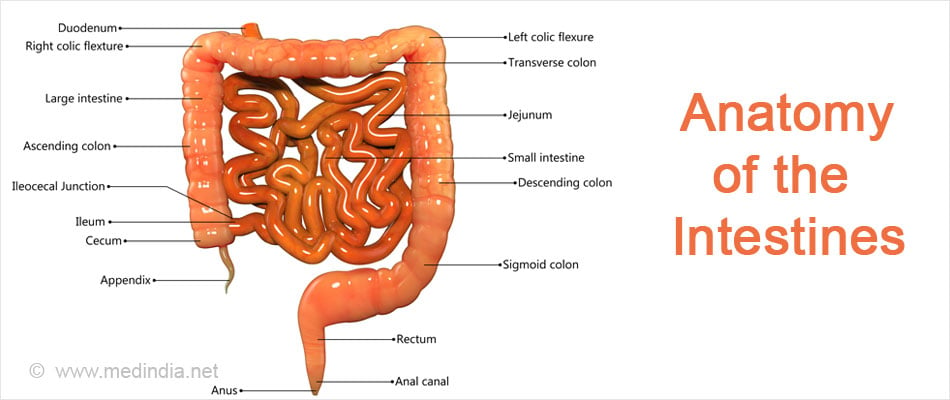

Intestines

The intestines are long tubes that are a part of the gastrointestinal tract or the GI tract. The GI tract is a continuous passageway connecting all the structures in between the mouth and the anus. All the food that reaches the stomach passes through the intestines. Intestines absorb nutrients and water from food and the waste is passed on to the anus for excretion. The intestines are categorized into the small intestine, large intestine and rectum. The small intestine connects the stomach to the large intestine. Mucosal cells cover the surface of the small intestine. They are called villi. It is the mucus and enzymes secreted by these mucosal cells which help in the absorption of nutrients. Mucus also acts as a bacterial barrier, thereby guarding the body against infections. The stomach digests food by the action of hydrochloric acid containing juices and secreted enzymes.

The normal length of the small intestine is 150–200 cm during 26 weeks of gestation; 200–300 cm at birth and 600–800 cm in adults. The small intestine performs the function of absorption of nutrients and fluid from food. 98% of the fluid is absorbed by the small intestine and only 2% is passed on as partially digested food to the large intestine. The large intestine changes this partially digested food into fecal matter, by absorbing the remaining liquid in it. This solid waste is passed on to the rectum to be secreted through the anus as stool.

The small intestine is further divided into three structural parts:

Duodenum - This is the first part of the small intestine where iron and minerals are absorbed.

Jejunum - This is the middle portion that has a greater absorption capacity as compared to the final section, ileum. 90% absorption of fats, proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins A, B, C, D, E, K and folic acid happens here. The jejunum also plays a significant role in the breakdown of sugar with the help of its enzymes. If a large part of the jejunum is removed, the absorption of all the above is impacted to a great extent. Also, the enzymes that break down sugars will be reduced resulting in decreased sugar absorption. Gut bacteria often use these unabsorbed sugars and produce lactic acid which might be released in the blood stream.

Ileum - This part of the small intestine absorbs water, electrolytes, bile salts and vitamin B 12.

There is an ileocecal valve which is a filter between the small and large intestine and connects the last part of the ileum and the first part of the large intestine (cecum). It is located at the end of the ileum.

- It slows down the mobility of the intestinal fluids into the colon.

- It also acts as a pressure gradient and prevents the large intestinal fluids from moving back up into the small intestine.

Large intestinal fluids are high in bacteria. Loss of the ileocecal valve

- Puts the small intestine at a risk of bacterial overgrowth which can further result in infection and acidosis.

- Results in rapid movement of food from the small intestine to the large intestine, which leaves no time for adequate absorption in the small intestine.

What are the Causes of Short Bowel Syndrome?

In juvenile short bowel syndrome, some children have a congenital defect where a part or all of their small intestine is missing.

The condition might also occur following surgical removal of a part of a child’s bowel owing to necrotizing entercolitis disorder that occurs in premature infants where portions of the bowel undergo tissue death.

It can also result from meconium ileus disorder in which the meconium, or the first stool of newborns blocks the ileum.

In adults, it is a majorly secondary condition and occurs due to surgically removing a large section of the small intestine due to:

- Bowel cancer

- Crohn’s disease, a disorder causing inflammation of digestive tract

- Gastroschisis, a disorder resulting in the intestines projecting out of the body through the umbilical cord

- Intestinal hernia, a hernia resulting in the small intestine popping out of the abdominal lining

- Intestinal injury

- Intussusception where a part of the intestine folds into another part of the intestine

- Midgut volvulus where a loop of intestine can twist around itself resulting in lack of blood supply to the bowel

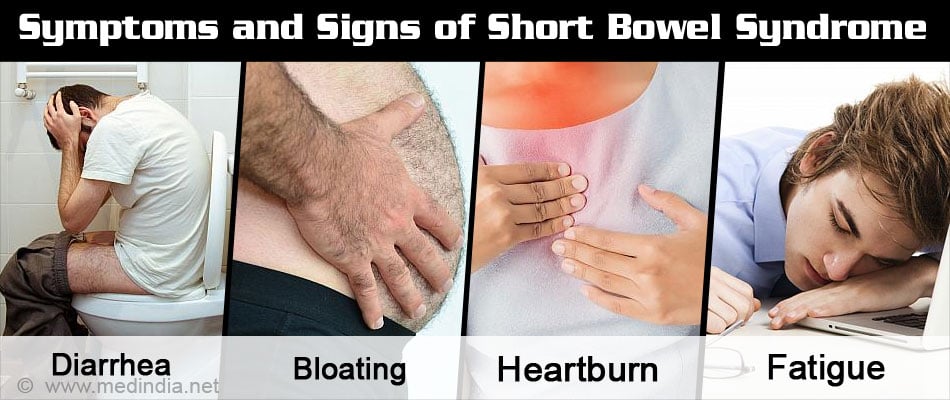

What are the Symptoms and Signs of Short Bowel Syndrome?

The most common symptom of short bowel syndrome is diarrhea. Diarrhea occurs due to unabsorbed fluid and unabsorbed bile salts. This further leads to dehydration resulting in electrolyte imbalance. Other symptoms include:

Severe dehydration that occurs if the diarrhea is not treated on time might result in further complications. Signs of severe dehydration are:

- Excessive thirst

- Dark colored urine

- Infrequent urination

- Lethargy

- Dry skin

- Dry mouth

- Dry tears in infants

What are the Complications of Short Bowel Syndrome?

- Malnutrition that can further result in swelling of the abdomen, dehydration, loss of muscle mass, peripheral edema and wasting of muscles of the temples giving them a hollow appearance

- Peptic ulcers

- Kidney stones

- Sepsis resulting from small bowel bacterial overgrowth

- Gallstones formation due to disturbed enterohepatic circulation of bile salts

- Renal stones formation due to fat malabsorption

- D-lactic acidosis due to stasis

Malnutrition also leads to several deficiencies

- Vitamin A deficiency leading to night blindness and abnormal dryness of the eyes

- Folic acid deficiency can lead to macrocytic anemia

- Vitamin B deficiency can lead to inflammation of the mouth and tongue, dry scaling of the lip, anemia, weakness of eye muscles, decreased or increased heartbeat, peripheral neuropathy and seizures

- Vitamin D deficiency can result in rickets in children and weakening of the bones, intermittent muscle spasms and paresthesias (abnormal tingling sensation) in adults

- Vitamin E deficiency can result in paresthesias, tetany, ataxia and vision problems

- Vitamin K deficiency can cause prolonged bleeding and a tendency to bruise easily

What is the Diagnosis for Short Bowel Syndrome?

The doctor starts the diagnosis with a detailed medical and family history of the patient. This is followed by a series of investigations:

- Blood test – This is done to test the level of electrolytes, minerals, and vitamins in the body. Full blood count, albumin, creatinine, liver function test or LFT, electrolytes, coagulation profile, vitamin D, vitamin B12, and Vitamin A tests are done. Blood levels of calcium, magnesium, trace elements, and blood pH are also monitored.

- Fecal Fat test – It measures the body’s ability to break down and absorb fats.

- X rays of small and large intestines – Used to detect the degree of narrowness of the large intestine that may occur due to blockage of partially digested food.

- Barium swallows - Patient drinks barium liquid which coats the esophagus, stomach and bowel. This helps in getting a clear picture of the anatomy of the bowel.

- CT Scan contrast – Contrast CT Scan is recommended since it helps visualize bowel obstruction and changes in small intestine with more clarity.

What is the Treatment for Short Bowel Syndrome?

There are three main goals of treating short bowel syndrome to maintain adequate nutrition, increase intestinal adaptation and to avoid complications. Recovery from short bowel syndrome depends on the section of the small intestine that has been removed and the level of damage that has occurred to the remaining part of the small intestine.

Nutrition:

- Oral rehydration is the first and foremost treatment for short bowel syndrome. It is primarily important to restore the lost electrolytes in the body to maintain homeostasis.

- Enteral nutrition is given to patients who are unable to eat. When the patient is hemodynamically stable and fluid management is stable, enteral nutrition is started in which liquid diet is passed through a feeding tube into the patient’s stomach. Patients with at least 30 cm of small intestine are more likely to survive on enteral nutrition.

- Parental nutrition is given to the patients who are also not able to eat. In parental mode, fluids are passed into the patient’s body through an intravenous route. Patients who are on parental nutrition for a very long time develop complications including bacterial infections, low bone calcium, thrombocytopenia, gallbladder disease, kidney disease and liver problems. Patients with less than 30 cm of small bowel need parenteral nutrition.

- Patients are recommended small frequent feedings and a diet rich in vitamins and minerals and low in sugar, fat, protein and fiber as they are difficult to digest.

Medications:

- Antibiotics are prescribed to prevent bacterial infection resulting from bacterial overgrowth in the colon.

- H2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors and anti-secretin agents are given to the patients to deal with over secretion of gastric acid.

- Choleretic agents are given to improve bile flow.

- Bile salts binders like ion-exchange resins help in controlling diarrhea.

- Hypomotility agents, antidiarrheal drugs, growth hormone and teduglutide help in slowing down the movement of food from the small intestine thereby enabling enhanced absorption time of nutrients.

- Somatostatin decreases gastric, pancreatic, and intestinal secretions.

- Prokinetic agents help in treating delayed gastric emptying.

Surgery:

- It is required in almost half of the patients at the later stage of the disease when the patient is on the verge of developing life threatening complications.

- It is useful in patients who develop strictures and partial obstruction.

- Intestinal inter-positioning is done which helps in delaying gastric emptying, slowing intestinal transit, and increasing absorption.

- Serial transverse enteroplasty is performed in children by creating a “zig-zag” shaped bowel that is longer resulting in food taking a longer time to move through the bowel, and enabling a greater chance of absorption.

- Intestinal lengthening and tapering procedures are done to increase absorptive surface area. Bianchi Procedure is one such procedure in which the small intestine is cut longitudinally, creating a segment of intestine twice the length and half in diameter without loss of the mucosal surface. This is indicated in cases of bacterial overgrowth and dilated bowel.

- Intestinal transplant is considered in patients who have developed complications and are non responsive to other treatments. The diseased small intestine is removed and replaced with one from a healthy donor. Transplant comes with its own set of complications which are far more difficult to manage, rejection being its first major complication.

Intestinal Adaptation

Intestinal adaptation after removal of part or whole of the small intestine starts 24-48 hours post surgery. Adaptation takes up to 2-3 years and lasts up to 11-12 years. The intestine changes in its width, functional capacity and morphology. Adaptation occurs in three phases:

- Active - It starts immediately after small intestine resection and lasts for about 1-3 months. At this stage, patient’s fluid output is greater than 5 liters per day. Patient is subject to dehydration, electrolyte imbalances and extremely poor absorption of all nutrients. Patient is solely dependent on parenteral and enteral nutritional feeds for adequate nutrition.

- Adaptation - It begins 12-24 hours after resection and lasts up to 1-2 years. 90% changes in morphology, width and functional capacity occur during this phase. The villi in the remaining small intestine increase in size resulting in increased absorptive area. The inside diameter of the intestine also increases. Parenteral nutrition is given throughout this period.

- Maintenance - The absorptive capacity of the remaining small intestine is at a maximum at this phase. Oral feedings are started.

As soon as the small intestinal surgery is done, doctors wait for the gastro-intestinal function to return. Intestinal feeds are gradually started through a nasogastric tube. Infants are fed partly through oral mode so as to establish their ability to suck. Intestinal adaptation begins quickly after loss of intestine. Therefore, small amounts of feeds are started early to stimulate adaption. Fluids are introduced first followed by elemental diets wherein all the nutrients are broken down into simplified forms so as to increase absorption. During hospitalization and at home, stools whether in infants or adults, should be monitored periodically. Key things to note are the amount of water and the presence of undigested food passed in stools, frequency and volume of stools.