- Mayo Clinic Staff. Sweet’s syndrome. Published Mar 6, 2018. Accessed April 9, 2018; Cited April 9, 2018.

- Raza, S et al. Insight into Sweet's syndrome and associated-malignancy: A review of the current literature. Int J Oncol. 2013; 42(5):1516-1522. - (https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2013.1874.)

- Sweet’s syndrome (Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). Updated April 2015. Accessed April 9, 2018; Cited April 9, 2018. - (https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2013.1874.)

- Oakley A. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Updated Sept 2015. Accessed April 9, 2018; Cited April 9, 2018. - (https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2013.1874.)

- Sweet syndrome. Published 2015. Accessed Mar 9, 2018; Cited Mar 9, 2018. - (https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2013.1874.)

- Cohen PR. Sweet’s syndrome - a comprehensive review of an acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Orph J Rare Dis. 2007; 2:34 - (https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-2-34)

- What’s the difference between infectious and contagious? Updated June 2014. Accessed April 10, 2018; Cited April 10, 2018. - (https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-2-34)

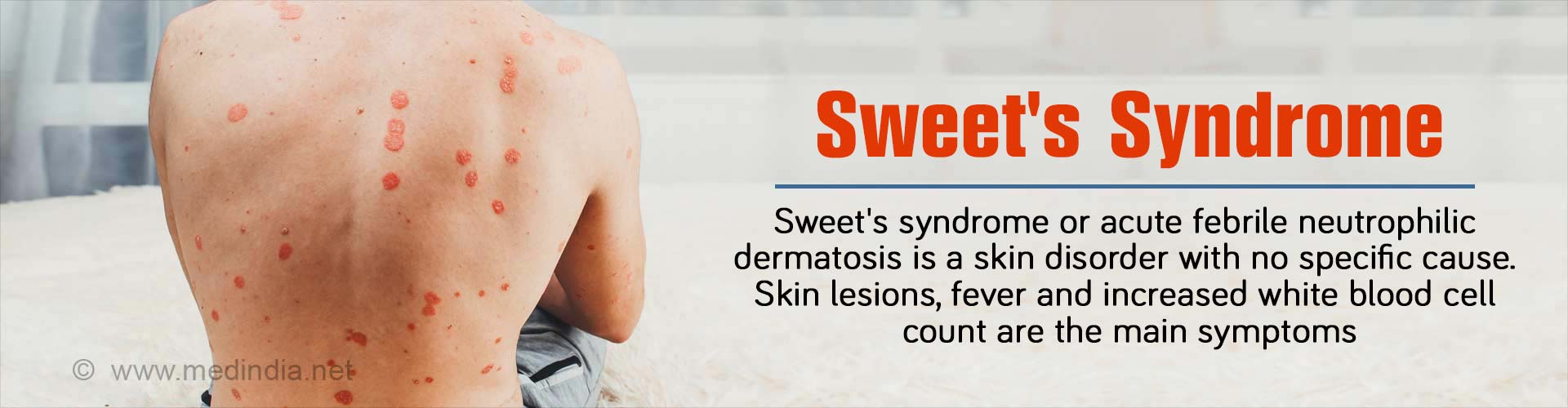

What is Sweet’s Syndrome?

Sweet’s syndrome is a skin disorder that is rare and characterized by fever, skin lesions or blisters, and an accumulation of infection-fighting white blood cells called neutrophils at the sites of skin lesions. Sweet’s syndrome named after its discoverer Dr. Robert Douglas Sweet (who described it in 1964) is also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. The skin lesions occur most often in the neck, arms, legs, and face.

Women (between 20 and 40 years of age) are often affected with Sweet’s syndrome but this condition is also seen in men and women of other ages too and can occur in any race. It is rare to find this condition in children.

Sweet’s syndrome can be classified into 3 subtypes based on the diagnostic features (see below)

- Idiopathic or classical – In this case, Sweet’s syndrome affects women more than men at a ratio of 4:1

- Drug-induced

- Malignancy-associated – Sweet’s syndrome that arises due to malignancy is observed in equal frequency in males and females.

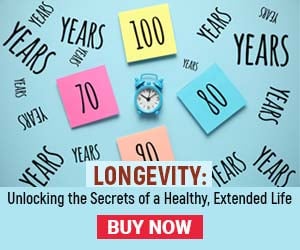

What are the Causes & Risk Factors of Sweet’s Syndrome?

The specific cause of Sweet’s syndrome is unclear. In nearly half the patients, there is no identifiable cause. There are speculations that the syndrome is the result of an allergic reaction. Below are some of the causes for the various subtypes of Sweet’s syndrome:

Classical: This condition arises due to:

- Hormonal changes (e.g. disorders of the thyroid gland, pregnancy)

- Upper respiratory infections

- Influenza-like infections

- Gastrointestinal diseases

- Yersiniosis (a bacterial infection causing diarrhea)

- Rheumatoid arthritis (joint inflammation)

- Inflammatory bowel diseases (e.g.

Crohn’s disease )

During pregnancy, classic Sweet’s syndrome occurs in the first or second trimester.

Malignancy-associated: In this case, solid tumors (e.g. breast cancer, adenocarcinoma, gastrointestinal tract carcinoma), blood cancers (e.g. leukemia,

Drug-induced: Sweet’s syndrome is found to develop after the use of anti-cancer medications, such as granulocyte-colony stimulating factor because this medication enhances neutrophil production. Examples of other drugs are decitabine, bortezomib, imatinib, among others.

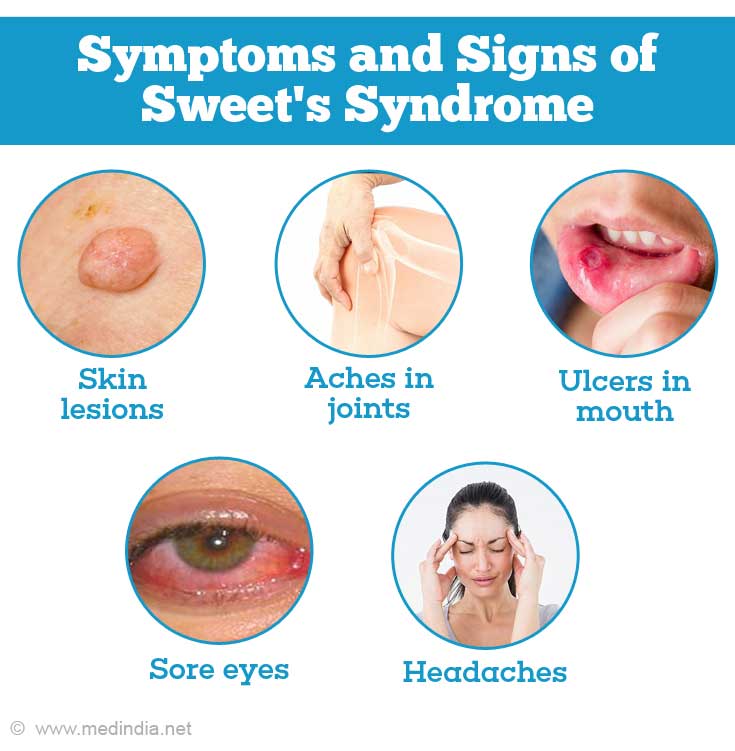

What are the Signs & Symptoms of Sweet’s Syndrome?

The symptoms of Sweet’s syndrome can occur over a range of a few hours to a few days. Some of the symptoms of Sweet’s syndrome are listed below:

- Skin lesions – raised pink to red tender lesions measuring 5-10 mm or larger and occasionally individual lesions coalesce to form larger plaques.

- Moderate to high fever – This may occur before, during or after the lesions. In some cases of malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome, there is no fever.

- Aches in joints

- Ulcers in mouth

- Sore eyes

- Other organs that may be involved include kidney, heart, liver, spleen, muscles, lungs, intestines, bones, and nervous system

- Headaches

- Hypersensitivity of skin – Lesions appear at sites of vaccination, sunburn, insect bites, cat scratches, biopsies or locations of catheter placement.

- Feeling unwell with exhaustion

- Anemia - observed in drug-induced and malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndromes. It is rarely observed in classical cases.

How is Sweet’s Syndrome Diagnosed?

Sweet’s syndrome is diagnosed based on history, physical examination, blood count and biopsy tests. Corticosteroids, potassium iodide and colchicine are first-line medications. There are different diagnostic criteria for the 3 categories of Sweet’s syndrome.

Classical and malignancy-associated Sweet’s syndrome are diagnosed based on 2 major symptoms and 2 out of 4 minor symptoms.

Major symptoms:

- The sudden appearance of skin plaques or nodules.

- Laboratory tests demonstrate a high neutrophil count, and biopsy of skin demonstrates predominantly neutrophilic inflammation without associated vasculitis (inflammatory cell collection around blood vessels)

Minor symptoms: If 2 out of 4 minor symptoms are observed along with the major symptoms, the doctor can confirm the diagnosis of classical Sweet’s syndrome. The minor symptoms are:

- A good response to medications, such as potassium iodide or corticosteroids

- High fever > 38°C

- Abnormal laboratory test results (e.g. > 70% neutrophils, positive C-reactive protein, > 8000 leukocytes, erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 20mm/hr)

- Symptoms occur after a gastrointestinal infection, an upper respiratory infection or vaccination, or symptoms are associated with pregnancy, inflammatory illness, solid tumors or blood cancer.

In the case of drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome, the diagnostic criteria, all of which have to be present include:

- High fever > 38°C

- Lesions reduce when medications are stopped or reappear following drug challenge

- Resolution of lesions following treatment with steroids

- Sudden development of nodules and plaques (raised tender skin that is red, pink or purple and is ³ half an inch or clustered together to form plaques)

- An association between ingestion of the drug and the development or recurrence of lesions

- Laboratory tests demonstrate a high neutrophil count and skin biopsy shows acute neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate without associated vasculitis.

Other Tests

- Since the lesions of Sweet’s syndrome are similar to those observed with other conditions, a skin biopsy of the lesions may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

- The lesions can also be assessed for infection with, either bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi or viruses.

- If involvement of other organs is suspected specialized blood and imaging tests may be done to look for any underlying cause

How is Sweet’s Syndrome Treated?

The syndrome heals without any treatment in some cases of classical Sweet’s syndrome but it may take either weeks or months. Corticosteroids either topical or oral form the mainstay of treatment. Treatment of any underlying condition such as inflammatory bowel disease or cancer will also help in resolution of symptoms.

First-line therapy

Corticosteroids – Doctors will first treat you with corticosteroids, such as prednisone at a single dose of 30 to 60 mg/day in the morning. When the symptoms begin to reduce, the dosage may be reduced by 10 mg/day over a period of 4 to 6 weeks. In some cases, the treatment may be prolonged for 2 to 3 months.

People who do not respond to other treatments may require intravenous treatment of corticosteroids, e.g. intravenous (1 hour) methylprednisolone sodium succinate (1000 mg/day) for 3 to 5 days. At the end of the intravenous treatment, an immune-suppressing drug or an oral dose of corticosteroid is given.

Symptoms of Sweet’s syndrome concentrated in a particular region (localized) are treated with topical corticosteroids on their own or combined with other treatments (e.g. 3 mg/ml to 10 mg/ml triamcinolone acetonide – single or multiple treatments; 0.05% clobetasol propionate as a gel, ointment, cream, or foam base).

Colchicine (oral daily dose of 1.5 mg) and potassium iodide (oral daily dose of 900 mg) are other effective drugs to treat Sweet’s syndrome. These are useful for people who are unable to take steroids due to high blood pressure or diabetes.

Second-line therapy

When corticosteroids, colchicine and potassium iodide are ineffective, other drugs, such as cyclosporine, indomethacin, dapsone, thalidomide, infliximab, chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, tumor necrosis factor, immunoglobulins, interferon-a, and clofazimine, are used on their own, following first-line therapy, or in combination with other treatments.

Side effects to any of the above medications should be assessed with the help of regular blood tests.

In the absence of treatment, classical Sweet’s syndrome lasts for weeks or months and in some patients, the skin lesions resolve on its own.

Other Treatments

- In drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome, symptoms are resolved when the medications are stopped.

- When malignant conditions are treated and go into remission or are cured, the symptoms of Sweet’s syndrome resolve themselves.

- Surgical interventions to treat solid tumors, renal failure or tonsillitis, also may help to resolve Sweet’s syndrome.

Recurrences are quite common, and treatment may need to be reinitiated until these stop. Rarely, the condition remains indefinitely and maintenance therapy for a prolonged period may be necessary.

How is Sweet’s Syndrome Prevented?

Sweet’s syndrome is the result of an underlying condition, such as inflammatory bowel disease, thyroid diseases or cancer. Managing and treating these conditions promptly, could help prevent the occurrence of Sweet’s syndrome.