- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (Lupus) - (https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/lupus/advanced)

- Lupus - (https://report.nih.gov/NIHfactsheets/ViewFactSheet.aspx?csid=47)

- Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine 19th edition - (https://report.nih.gov/NIHfactsheets/ViewFactSheet.aspx?csid=47)

- Gordon C et al. The british Society for Rheumatology guideline for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults: Executive Summary. Rheumatology, Volume 57, Issue 1, 1 January 2018, Pages 14–18 - (https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex291)

- Hahn bH. American College of Rheumatology: Guidelines for Screening, Treatment, and Management of Lupus Nephritis. Arthritis Care & Research 2012; 64(6):797– 808. DO - (10.1002/acr.21664)

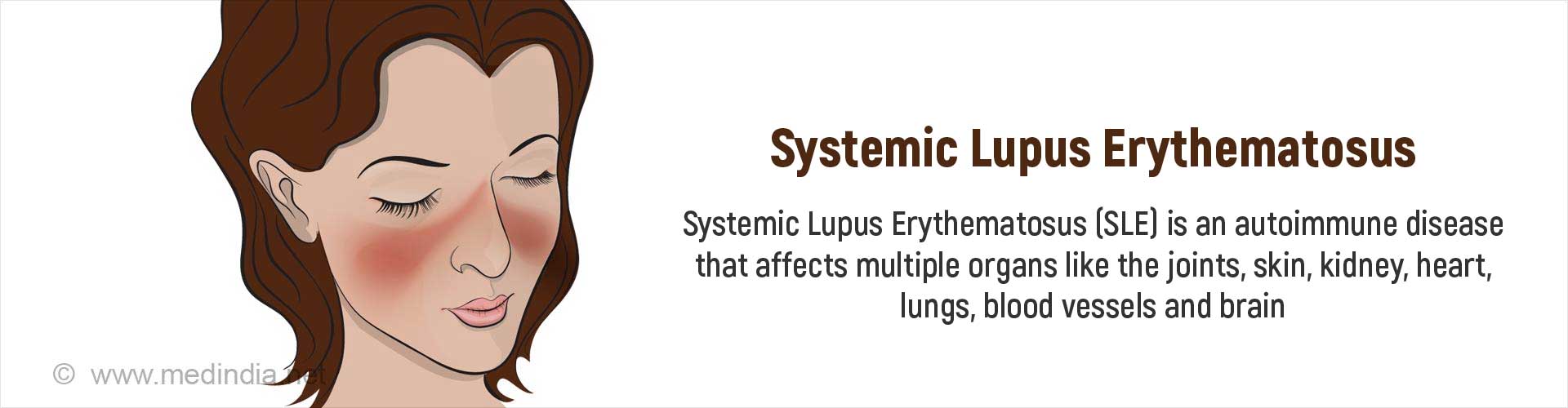

What is Systemic Lupus Erythematosus?

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic disease with many manifestations. It is an autoimmune disease in which the body's immune system is directed against its own tissues (the body harms its own healthy cells and tissues) leading to inflammation of various parts of the body. It can occur at all ages, but is more common in young women. Though it can run in families, the risk that a close relative will also have lupus is not very high.

What is the Cause of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus?

Lupus is a complex disease, the cause of which is unknown. The body forms antibodies against its own tissues. The antibodies attach to certain protein molecules resulting in immune complexes which contribute to inflammation and tissue injury in different parts of the body.

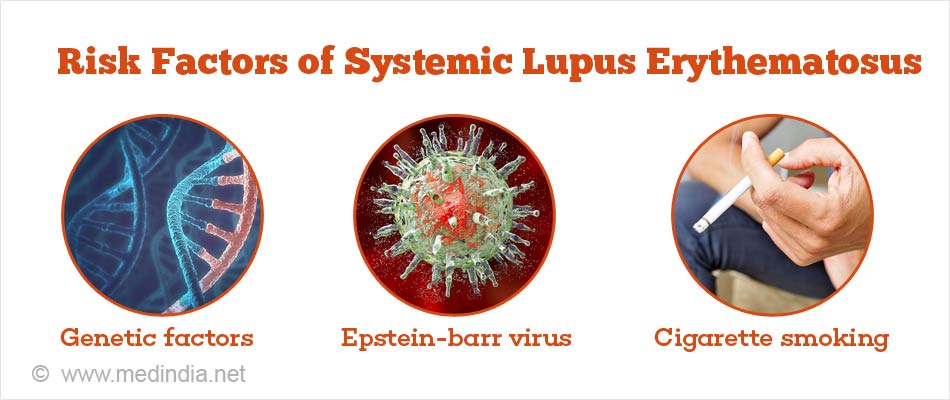

The risk factors for SLE include the following:

- Genetic factors: Multiple genes, even up to 45 in number, have been suggested to be associated with SLE.

- Gender: SLE affects women in the child-bearing age in 90% of the cases, although it can affect children and older individuals as well. A hormonal effect possibly increases the risk. The presence of fever, joint pain and rash in a young woman should prompt a suspicion for SLE.

- Environmental factors: Exposure to ultraviolet light may trigger flares. Other conditions that increase the risk of SLE include infection with Epstein Barr virus, cigarette smoking, and prolonged occupational exposure to silica.

What are the Symptoms of SLE?

Each person's experience with lupus is different, though patterns exist that permit an accurate diagnosis. The symptoms can range from mild to severe and may come and go over time, resulting in flares and periods of remission. Lupus can affect many parts of the body, including the joints, skin, kidneys, heart, lungs, blood vessels, and brain.

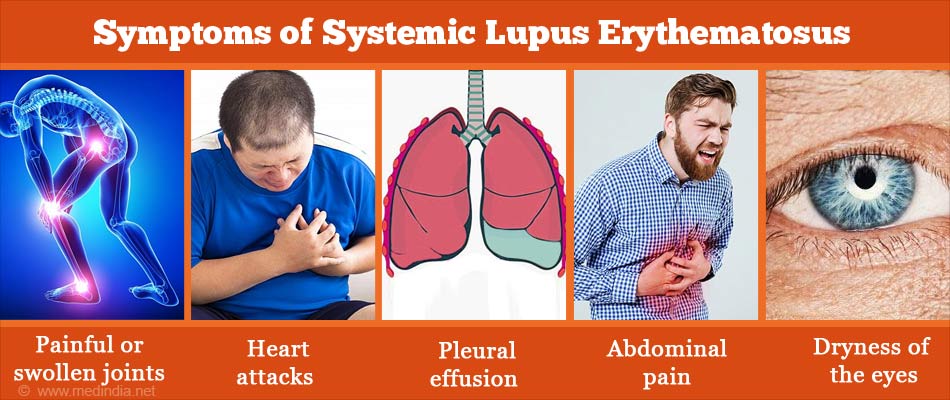

Common symptoms of lupus that occur during flares include the following:

Joints and muscles: SLE causes painful or swollen joints especially in the hands, wrists and knees. The pain may be mild to severe. Avascular necrosis (damage due to reduced blood supply) of the head of the thighbone in the hip may occur either due to the disease or as a side effect of medications. Muscle pain and weakness may be noted.

Skin and mucous membranes: A characteristic skin rash called the butterfly or malar rash may appear across the nose and cheeks. The rash is sensitive to light (photosensitive), and could be flat or slightly raised. Discoid plaques may be noted, which may show scaling and follicular plugging. The rash may also occur on other parts of the face and ears, upper arms, shoulders, chest and upper back. The rash may be mild or severe. Small ulcers may occur inside the mouth or the nose.

General symptoms: These include unexplained fever, extreme fatigue, and weight changes.

The following systems in the body also can be affected by lupus:

Kidneys: SLE causes inflammation of the kidneys, referred to as lupus nephritis, which can vary from a mild to a severe condition. Though some individuals may experience swelling around their ankles or puffiness of their eyes, it may not cause any symptoms in the initial period and may be detected only on an abnormal urine or blood test. It is therefore important to monitor a patient for kidney disease once the diagnosis of SLE is made.

Central nervous system: SLE can affect the brain or the spinal cord resulting in symptoms of headaches, dizziness, memory disturbances, stroke, seizures or changes in behavior.

Cardiovascular system: SLE may cause mild-to-severe inflammation of blood vessels, a condition called vasculitis. It can also increase the risk of atherosclerosis as well as blood clots, which could predispose to transient ischemic attacks, heart attacks or strokes. It can cause inflammation of the heart (myocarditis or endocarditis), or the tissue surrounding the heart (pericarditis), causing chest pain or other symptoms. A reduction in blood counts may also be noted.

Lungs: SLE may affect the tissue lining the lungs resulting in pleuritis or pleural effusion, or the lung itself, sometimes even resulting in lung fibrosis, shrinking lung syndrome or intra-alveolar bleed.

Digestive tract: Patients may experience nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain during a flare along with an increase in liver enzymes. Inflammation of the blood vessels in the intestine can predispose to life-threatening conditions like bleeding, perforation and sepsis.

Eye: SLE can affect the eye resulting in sicca syndrome (dryness of the eyes and the mouth), retinal vasculitis and optic neuritis (inflammation of the nerve responsible for vision) which may threaten vision.

How can SLE be Diagnosed?

Lupus is diagnosed based on a combination of clinical features and laboratory tests.

1. Antinuclear Antibodies (ANA):

More than 95% of SLE patients test positive for autoantibodies called antinuclear antibodies (ANA) in their blood. It must however be remembered that ANA may be positive in some non-lupus cases as well, which include infections and other rheumatic diseases.

2. Other Autoantibodies:

The presence of other antibodies in the blood like anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), anti-Sm (anti-Smith), anti-RNP, anti-Ro (SSA), and anti-La (SSB) is more specific for SLE, though these may not be present in all SLE patients. A positive anticardiolipin antibody test may indicate an increased risk of blood clot formation and miscarriages in pregnant women with lupus.

3. Biopsy

A biopsy of the skin or kidneys may be required if those systems are involved.

4. Other Investigations

Other investigations that are used to monitor the progress of the disease include:

Blood tests: Blood tests done include complete blood count, blood chemistries, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and complement level estimation.

Urine examination: Urine examination, especially to measure the presence of protein, gives an indication of kidney involvement.

Imaging tests: Imaging tests that include x-ray of the bones and joints, CT scan, MRI of the brain, and echocardiography of the heart may be done depending on the organ involved.

According to the American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria, the presence of four or more of the following features, either simultaneously or successively, is necessary for the diagnosis of SLE:

- Malar rash

- Discoid rash

- Oral ulcers

- Arthritis

- Photosensitivity

- Serositis in the form of pleuritis or pericarditis

- Blood disorder, with reduced red blood cell, white blood cell or platelet counts

- Kidney involvement

- Brain involvement in the form or seizures or psychosis

- Positive antinuclear antibodies

- Positive immunologic tests like anti- dsDNA, anti-Sm antibodies or antiphospholipid antibodies

How can SLE be Treated?

SLE cannot be cured. Treatment is usually directed at controlling the symptoms of remissions and preventing organ damage.

The treatment of SLE depends on its severity – SLE may be mild, moderate or severe, or may occur as flares. The following is a summary of the guidelines issued by the Royal Society of Rheumatology for its treatment.

Mild SLE

Mild SLE usually involves the skin and mucous membranes, joints or the pleura (tissue covering the lungs), but is not associated with life-threatening organ involvement. The symptoms may include fatigue, rash on the cheeks, diffuse hair loss, mouth ulcers, joint or muscle pain, and a platelet count of between 50 and 149 × 109/l.

Drugs that can be used for the treatment of mild SLE include:

- Initial treatment can be with local corticosteroid, oral prednisolone ≤20 mg daily for 1–2 weeks, or intramuscular or intraarticular (injection into the joint) injection of methyl-prednisolone in a dose ranging from 80 to120 mg.

- In addition, the disease-modifying drugs hydroxychloroquine and /or methotrexate and/or short courses of NSAIDs (non-steroidal painkillers like ibuprofen and diclofenac) may be used.

- Low dose prednisolone (less than or equal to 7.5 mg/day), hydroxychloroquine and/or methotrexate may be used for maintenance treatment. Corticosteroids may be used locally on the skin or can be injected into the joints for arthritis.

- High–Sun Protection Factor (SPF) sunscreen along with avoiding sunlight is advised to prevent skin lesions.

Moderate SLE

Moderate SLE is characterized by fever, rash up to 2/9 body surface area, cutaneous vasculitis (inflammation of the blood vessels of the skin), hair loss with scalp inflammation, liver or joint disease, inflammation of the pleura or pericardium (the tissues surrounding the lungs and the heart, respectively) and a platelet count of 25–49 × 109/l. Moderate SLE requires the following drugs:

- Corticosteroids in the form of higher doses of prednisolone (up to 0.5 mg/kg/day), or the use of intramuscular or intravenous injections of methylprednisolone.

- Methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine or other calcineurin inhibitors may be used in addition to hydroxychloroquine for patients with skin or joint disease, vasculitis or low blood counts.

- For cases that do not respond to the above treatments, belimumab or rituximab may be tried out.

- Maintenance treatment is with prednisolone, hydroxychloroquine, and azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil or cyclosporine.

Severe SLE

Severe SLE is a life-threatening condition that can affect vital organs including the kidneys and the brain. The patient may present with rash involving more than 2/9 body surface area, muscle pain, severe inflammation of the pleura and/or pericardium with fluid accumulation, fluid accumulation in the abdomen, involvement of the intestines, brain, spinal cord, and optic nerve, and an extremely low platelet count of less than 25 × 109/l. The presence of infection should be ruled out in these patients.

- Intravenous methylprednisolone or high-dose oral prednisolone (up to 1 mg/kg/day) may be required for initial treatment.

- Immunosuppressive drugs that may be used include mycophenolate mofetil and cyclosporine for lupus nephritis and refractory severe non-kidney disease in addition to the corticosteroid treatment in addition to hydroxychloroquine.

- The biologic therapies belimumab or rituximab may be used for patients who have failed to respond to the immunosuppressive drugs or cannot use them due to side effects.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis (removal of antibodies from the plasma) may be required for patients with low blood counts not responding to treatment, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (due to low platelet levels), rapidly deteriorating acute confusional state and the catastrophic variant of APS (antiphospholipid syndrome).

- Anticoagulation may be needed for patients with thrombotic manifestations.

- Maintenance treatment is with prednisolone and azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil or cyclosporine, along with hydroxychloroquine.

The treatment for flares depends on the severity of the underlying disease. Most drugs except hydroxychloroquine can be eventually stopped once the patient achieves stable remission. Vitamin D supplements are usually required since these individuals avoid sun exposure due to photosensitivity.

The American College of Rheumatology issued guidelines for the screening, treatment, and management of kidney involvement due to lupus in adults in 2012. Some salient features include:

- All patients with clinical evidence of active kidney disease that was previously untreated should undergo a kidney biopsy to assess the kidney changes and classify the disease unless it is strongly contraindicated.

- All patients with kidney disease should be treated with hydroxychloroquine unless contraindicated.

- All patients with protein loss in the urine of more or equal to 0.5 gm per 24 hours should receive ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers.

- The blood pressure should be maintained at less than 130/80 mm of Hg and the LDL cholesterol at less than 100 mg/dL with statins.

- Women in child-bearing age should be counselled about the risks during pregnancy due to the disease as well as the treatments.

- Mycophenolate mofetil (2–3 gm total daily orally) or intravenous cyclosporine along with glucocorticoids should be used in patients with ISN (International Society of Nephrology) Class III/IV lupus glomerulonephritis. These are not required for class I and class II disease.

- Class V lupus nephritis is treated similarly when found simultaneously as class III or IV. Class V lupus nephritis present alone should be treated with prednisone (0.5 mg/kg/day) with mycophenolate mofetil (2-3 grams total daily dose).

- Patients who respond to treatment should be maintained with azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil.

- In patients who do not respond to initial treatment in 6 months, the treatment can be switched to either mycophenolate mofetil or cyclosporine (depending on which was the initial treatment) along with intravenous glucocorticoid pulses for three days. Rituximab is also an option in these patients.

- Thrombotic microangiopathy, a condition that affects blood vessels, can be treated primarily with plasma exchange therapy in patients with lupus nephritis.

- Pregnant women with mild systemic activity may be treated with hydroxychloroquine. Clinically active nephritis or substantial extra-renal disease activity can be treated with glucocorticoids, with azathioprine if necessary.